Lula wins but Brazil will have to go to a second round

JUAN MIGUEL MUNOZ

São Paulo

Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva came close to reaching half plus one of the votes, but he did not get it in the first round. Brazil will go to a second round on October 30 to decide who will be the country's next president.

With 99,72% of the votes counted, Lula got 48,35% and Jair Bolsonaro, who was stronger than the polls showed, reached 43,26%, in one of the most bitter elections ever dog face of the last decades.

"We are going to win, this is just an extension," Lula said after learning the results a few hours after an election day marked by queues of voters, which took place relatively calmly.

Before, when going to vote, he had remembered his time in prison: “It is an important day for me. Four years ago I couldn't vote because I was the victim of a lie. I want to help my country return to normality.”

Bolsonaro, a conservative to the core, and the former leftist president, who governed the immense country between 2003 and 2010, faced each other dog-eat for the presidency of the most populous (215 million) and largest country in Latin America. They deeply hate each other. And that animosity has permeated supporters of both leaders, especially Bolsonaro supporters, some of whose most fiery loyalists have stabbed or shot rivals from the rival party. Both leaders are widely rejected by a large part of the population, but the polls gave Lula an advantage of up to 17 points (48% compared to 31% in the poll a week ago).

During the campaign, the incumbent president attacked his rival – whom he describes as a "nine-fingered thief" for the amputation of a little finger that Lula suffered during his time as a metallurgical industry worker – with continuous accusations of corruption in the period of government of the Workers' Party. It matters little to Bolsonaro that the justice ruled Sergio Moro's partiality and that the sentences were annulled. The president shouts from the rooftops that Lula intends to return to the scene of the crime.

The ultra-conservative president, who has defended torture, the dictatorship (1964-1985) and who is proud in public of his erections, based his campaign on the defense of traditional moral values, deeply rooted in Brazil. He has the majority support of the faithful of the countless evangelical churches, which have been adding followers for decades at a breakneck pace. And he assures that in 2023 he will maintain the Brazil Aid – an aid of 600 reais, just over 100 euros – for the most needy families, a program that Lula actually implemented many years before under the name of Bolsa Familia. Bolsonaro takes a toll on his management of the Covid pandemic, something that people who supported him in 2018 and who now probably have not voted for the 67-year-old leader born in the interior of the State of São Paulo, reproach him for.

For his part, Lula from Pernambuco, at the age of 76, recalled again and again his two four-year terms in which Brazil, helped by the boom in raw material exports, managed to lift tens of millions of people out of poverty. . Now, he promises that he will once again include the poor in the country's budget, that he will protect the Amazon, and is extremely cautious when he speaks about abortion, the rights of the LGTBI collective or the religious preferences of citizens.

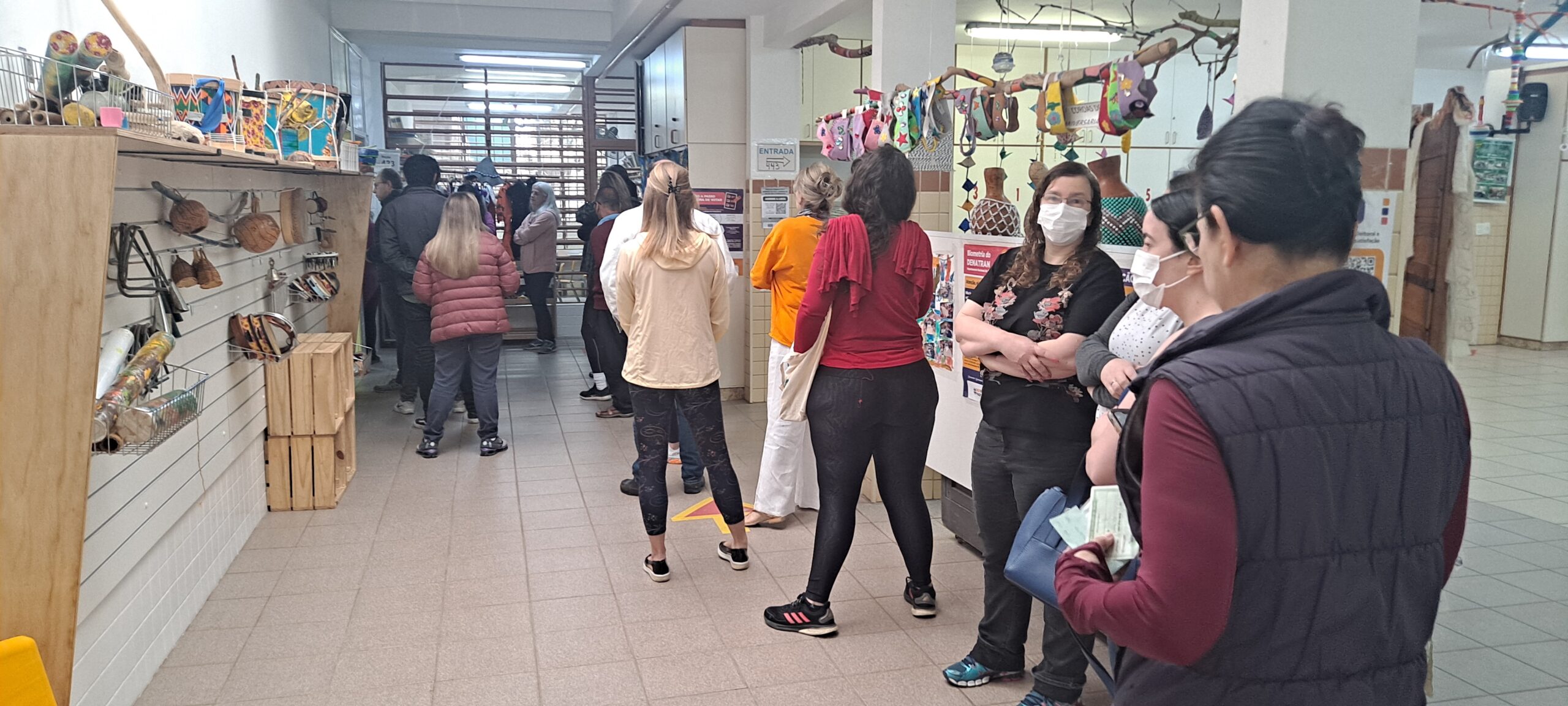

Photo: Juan Miguel Muñoz, also the one who heads this information

If the result of the second round can be unknown, the questions arise for the day after. Cheered by his loyalists, who demand the closure of Congress and the Supreme Court at rallies, Donald Trump's emulator has cast doubt on the electronic counting system, in which the military participated. For at least a year the specter of the coup d'état has been hanging over Brazil. It is very unlikely. But it is more likely that, in the event of Bolsonaro's defeat, his supporters will not sit idly by. The president has not stopped sowing the seeds for a convulsive post-electoral situation to emerge. The Supreme Court is the target of his wrath. Many citizens predict that some riots are inevitable.

On September 7, the bicentennial of the independence of Brazil was celebrated. Bolsonaro brazenly used the official acts – to which the presidents of Congress, the Senate and the Supreme Court did not attend – as one more rally of his electoral campaign. And the next day, the president refused to attend the official bicentennial events in Brasilia. He also turned into a rally his speech before the United Nations General Assembly and his visit to the Brazilian Embassy in London, the city he attended for the funeral of Elizabeth II. The disputes with the Supreme Court have been a constant in the four years of his mandate. Never in the 200 years since the independence proclaimed by Pedro I has Brazil definitively resolved the limits on the powers of the executive, legislative and judicial powers. And the role that the military establishment can play in political life remains unclear – the 1988 Constitution leaves ample room.

Drastic changes cannot be expected whoever is the winner in the elections. Surely, Lula's victory will mean a marked improvement in Brazil's relations with other countries, but the economic situation will not allow Lula to embark on social programs as broad as those he applied at the beginning of the century. Although Brazil —unlike other Latin American countries, such as its neighbor Argentina— maintains a good deal of order in its public accounts, an adjustment in budgets and a certain containment of expenses is imposed.

Without a far-reaching fiscal reform, it is a chimera to profoundly transform the Brazil of the favelas and the poor outskirts of the cities, where the vast majority of the population lives. "Do you know how much the rich and the very rich pay [in direct taxes] in this country?" Economy Minister Paulo Guedes asked himself at the beginning of the year during an interview on a television channel. “Zero”, this liberal minister and staunch supporter of privatization responded to himself.

Social inequality has always been overwhelming in Brazil, and serious attempts to promote deep changes in favor of the underprivileged classes met with the rejection of the privileged elites, always triumphant. The social transformations promoted by President Getulio Vargas in the 40s and 50s of the last century; the deepest reforms –agrarian, fiscal, administrative– promoted by João Goulart at the beginning of the 60s were aborted by the military coup of 1964. Lula, much more prudent, ended up in jail, and Dilma Rousseff, ousted in the Congress for alleged accounting irregularities that were officially archived last week.

“We have nothing to celebrate. It's 200 years of what? Of injustice, of hunger, of racism, of oppression? We are repeating the same mistakes and there are only small palliative measures, not structural changes… In several respects we are in the XNUMXth century. Racism is an example,” filmmaker Luiz Fernando Carvalho recently commented in the Folha de São Paulo newspaper.

Juan Miguel Munoz is a journalist and lives in Brazil