Coup convulsion at the beginning of Lula's term

JUAN MIGUEL MUNOZ

São Paulo

Brazilian democracy suffered a severe shock on January 8, an attempt or project of a coup that has precedents throughout the two centuries of history of this continental country exclusively when the president in office leans to the left. The vandal assault on the headquarters of Brazilian institutions by coup fanatics has unleashed a whirlwind of political and judicial events whose consequences are still unpredictable.

As soon as the protest was submitted, on January 8, President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva had to adopt the first important decision. And he opted for federal intervention in capital security. That is to say, the Government of the nation took charge of the negligent police forces, or rather colluding, with the Bolsonaro assailants, who razed the Executive, Legislative, and Judicial palaces. He ruled out the so-called Guarantee of Law and Order, which implies the intervention of the Army in the maintenance of public peace. Lula does not trust.

But it was not only Lula and his government who got down to work. The hyperactive Supreme Court judge, Alexandre de Moraes, decided to temporarily dismiss for 90 days the governor of the Federal District, Ibaneis Rocha, who in turn had removed from office the Secretary of Public Security of Brasilia, Anderson Torres, a fervent Bolsonaro supporter. former Minister of Justice who was on vacation -coincidence?- in the United States on the day of these proceedings.

The negligence, if not the involvement in the altercations, of Rocha and Torres is difficult to avoid. Throughout the week it was learned that Rocha, also a Bolsonaro supporter, had received letters two days before from the Federal Police and the intelligence services in which it was clearly explained that the far-right protesters could do what they finally did. It was well known that the situation was dangerous. But those responsible for security did nothing. Only a few agents stood up to a mob that easily pushed them out of their way on the way to Congress. Lula's government was also aware of the situation, justifying its inaction by saying that security powers fall on the authorities of the Federal District.

Judge De Moraes continued with his decisions and ordered the immediate arrest of Torres the moment he returned to Brazil. That's how it went. Since Saturday, he has been sleeping behind bars in a Military Police battalion in Brasilia. As the more than a thousand people -several hundred have been released- arrested for their participation in the riots sleep in a gym. It is being investigated who financed this crowd that had certain services in their camps and who were paid to travel to Brasilia, mainly from the interior of the State of São Paulo and from the southern State of Paraná, bastions of the most reactionary ultra-right.

An obvious problem is that in many institutions -especially the Armed Forces and the Military Police, depending on each State- the supporters of the coup are firmly established. Even in the Attorney General's Office (PGR), its head, Augusto Aras, appointed by Bolsonaro, was reluctant to undertake any investigation. The president of the Senate, Rodrigo Pacheco, had to go to the headquarters of the PGR to urge Aras to take action on the matter.

But there is more. On Friday, January 13, the prosecutor's office orders Bolsonaro to be included in the investigation of the altercations due to his eventual incitement to commit crimes. And this hours after he was at the residence of Anderson Torres, his former Minister of Justice, a legislative project that established the intervention of the Superior Electoral Court during the period of the elections. Added to this are the four years of discrediting the institutions by Bolsonaro and his acolytes; the requests of ministers for the members of the Supreme Court to be arrested; the camps in front of the headquarters of the Army headquarters in many cities of the country demanding the military coup after the electoral defeat; the blessing of the chiefs of the three arms to these demonstrations; the former president's support for these coup protesters, and Bolsonaro's own statements that he acknowledged at the end of December that he had tried everything until the last day to prevent Lula's access to the presidency. Facts that lead many analysts to consider that the coup is being prepared for a long time. And that the process is not over.

The professor of Ethics and Philosophy, Renato Janine Ribeiro, wrote in Folha de São Paulo: “The mob that invaded Planalto, a mixture of perfect imbeciles, who generated evidence against themselves in the networks,… are no more than cannon fodder… Did they intend to seize power? No. They were financed to create a social upheaval.” The author believes that some deaths were necessary for a military regime to be imposed: "We narrowly escaped that... It was a complete failure, but it may have been a dress rehearsal for the next coup."

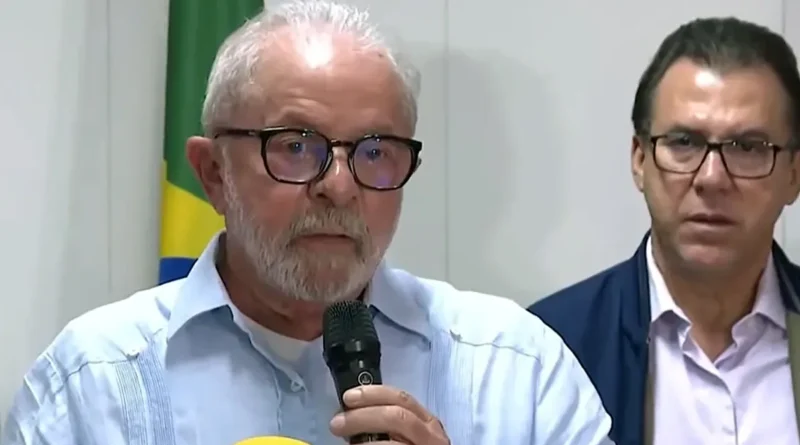

The president, in a meeting with journalists on Thursday, assured that he had lost confidence in the military and stated that “the armed forces are not the moderating power they think they are. They have a role in the Constitution that is the defense of the Brazilian people and their sovereignty…”.

The president alluded to a constitutional figure in force during the Brazilian empire, after independence in 1822. In the first Constitution of Brazil (1824) it was established that the emperor, Pedro I (1822-1831), had this moderating power, which he wasn't really just moderating. The monarch could name and dismiss the Government and dissolve the legislative Chambers when he deemed it appropriate. Pedro II (1840-1889) frequently exercised that prerogative, even forming governments without the support of the Assembly. The Army, which put an end to the monarchical regime in 1889 and expelled the imperial family into exile, has played that role ever since, in the opinion of numerous historians, political scientists and analysts.

As soon as the republic was proclaimed, the first two presidents were marshals. But there were more uniformed men at the head of the country (Hermes de Fonseca, Eurico Gaspar Dutra) before the military dictatorship between 1964 and 1985. The military deposed Getulio Vargas in 1945 and João Goulart in 1964, when they announced the application of clearly leftist policies. “The abode of the coup hydra is in the Armed Forces, which have exercised guardianship over the State since the Paraguayan war (1965-1970). This institution came under the control of uniformed men eager to assume the direction of the State, now through institutional channels, associating with a weakling [Bolsonaro] passionate about the dictatorship of the generals”, the journalist Breno Altman opined in Folha de São Paulo. "There will only be stability when the nest of snakes is swept from the barracks," added Altman.

If so, that stability is not going to come any time soon.