The abysses of Latin America

MARCELO CANTELMI

Buenos Aires

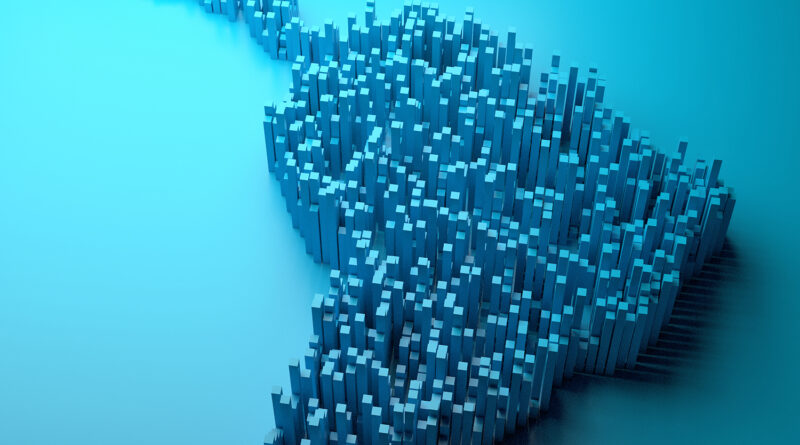

Latin America, the most unequal region in the world, is currently going through a series of phenomena as central as they are contradictory. The chronic economic crisis that defines this space was expanded oceanically with the pandemic and later by the financial effects associated with the brutal Russian war against Ukraine. The positive part of this phenomenon of growing shortages is that it largely dissolved the bases of support for a populism of socialist presumption that had been growing in the previous decade, particularly from Venezuela and Cuba and even Argentina, supplanting and overthrowing the old formulations real left. The notions of a plebiscitary democracy, which modified the concept of the election to pure patrimonialism for the sake of a mere endorsement of the leadership, a classic of Chavismo, lost ground due to the financing crisis. The same is experienced by Kirchnerist Peronism in Argentina or the current chaotic drift of the stage of President Miguel Díaz-Canel in Cuba, with the island stuck in an orthodox and disorderly turn that fuels an unpredictable social protest.

Populism in the region usually sought to associate itself with crises to retain its space of power and managed to float based on a strong pull in income from the sale of food or energy commodities. These flows were applied to subsidy structures among other benefits to maintain the initiative, which caused many of these national structures to grow but not develop. Argentina squandered in the so-called "earned decade" more than 160 billion dollars in subsidies to the rates of the middle and lower middle classes to support the Kirchnerist vote, which largely explains the unique inflationary alley that encloses that country, with a cost of living higher than that of Venezuela and a new enormous backwardness in its educational, health and future levels. As in Europe on the right, these models have been voluntarist in nature, they came to power as a response to the frustration of the representativeness crisis and in practice they exhibited absolute inefficiency due to their resistance to merit and the academy.

The data from ECLAC, the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, dependent on the UN, are ominous about how these borders survive today. In its latest report, it maintains that the region is registering a low growth trend similar to that of even before the pandemic. The economy this year 2022 would be around an expansion with a ceiling of 2,7%. The disaggregated information indicates that South America would be around 2,6% at the end of 2022 against 6,9% in 2021. Central America and Mexico, 2,5% against 5,7% last year. The report also pointed to the conflict with Ukraine, which intensified the rise in commodity prices observed since the second half of 2020, reaching historic levels in some cases. He maintains that for the region the effect is mixed and projects a 7% drop in the terms of trade of basic products.

Inflation, meanwhile, exhibited a regional average of 8,4% on an annual level measured in June 2022. An idea about the scope of this number is indicated by the fact that it grows twice as much compared to the indicator registered throughout the extensive period that goes from 2005 to 2019. But with cases of 100 percent annualized as projected for Argentina.

The generalized process of decapitalization broke down the political proposals, a phenomenon with a still confused dynamic. It is clear that at this stage in the region the left has virtually disappeared into the hands of different forms of the right, from the social democratic center to the extremes. The movements that perceive themselves as socialist or leftist have derived to caudillo formats in many cases with a high concentration of income in minorities associated with the regimes or directly turned into dictatorships of a classic civic-military style such as Daniel Ortega's Nicaragua, which he imitates in detail. the Somoza tyranny he helped fight.

Let us remember that the left was originally conceived as a tool to improve the distribution of income through a present State that would take care of that administration. That is precisely what has disappeared. Countries like Argentina, confront 60% of the population in poverty and without possibilities in the future through a solution that resolves this structural deterioration. The same thing happens in other borders where the State is, in the same way, a disappeared structure and the concepts of left, revolution or socialism are used as a Teflon against the denunciations of human rights violations or the rampant corruption that has marked these processes and their enormous deterioration in almost all the countries where they have spread.

Faced with these abysses and in relief of populist opportunism, timid alternatives of a more mature tone are beginning to emerge with respect to fiscal responsibility, growth programs and openings to multiply employment with bases similar to social democratic models. This is very good news that could indicate an eventual stage of maturation in the region. This is what is seen in the cases of the new Chilean center-left government of Gabriel Boric, the brand-new Colombian of Gustavo Petro, and what former president Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva hints at in Brazil with a view to the October elections. . This former metallurgical worker, who governed two terms with a liberal administration generating the highest historical rate of profit for corporations and private banks, now aims to return to power in his country and has ideological battles with his party, the PT, so that It occurs to them to propose repealing the law of independence of the Central Bank approved last year or actions against the business community.

The campaign in the second largest economy in the hemisphere after the United States is eloquent in that the discussion is not ideological, except for President Jair Bolsonaro's attacks on his rival, but about management efficiency. Which of the two has the greater capacity to balance the country's accounts and regenerate the model of capitalist accumulation. Recently in a meeting with the industrialists of São Paulo, the FIESP, a comfortable place for Lula since it is chaired by Josue Gomes, the son of his former and now deceased former vice president, José Alencar, the former president promised to defend the income of the entrepreneurs, and raised as Boric, the importance of fiscal responsibility. It is not possible, he said, to spend more than you earn, a no-brainer in most parts of the world, but not so much in those parts.

The Chilean leader, in turn, has even argued that inflation or welfare plans of the type that flood the economy of Argentina, are a perverse phenomenon that must be avoided. Lula's PT maintains that there is a coincidence with that argument. The Colombian Petro, for his part, has put together a cabinet with a clear centrist profile, particularly with his Economy Minister, academic José Antonio Ocampo, whose appointment was praised by the markets. In the same way, that the colleague of the branch in Chile, Mario Marcel, a prominent former president of the Central Bank. Everything seems to converge to a pragmatic centrism of the Uruguayan style of the leftist Broad Front center where a former president like José Mujica argued that the businessman must be defended "like a cow that must be fed and not butchered because we are left with nothing".

The perspective of these models is auspicious but complex. Not only because it is not clear to what extent they will hold up against internal pressures, especially from their allies who support that notion of a magical progressiveness that comes from a notion that intellectuals call "ideological obituary" due to the persistence of embracing dead ideas. . The Chilean Boric comes from a serious defeat due to the massive rejection of the new Constitution that a minority drafted as a government program rather than a Magna Carta and on that path ignored more than 50 percent of the country prevented from intervening in the text now refused. The electoral coup eroded the power of the government.

Another phenomenon to take into account is the general situation of the regional and world economy that reduces the room for manoeuvre, in addition to the legacy that the past brings. In this sense, a study by Americas Quarterly last July is interesting, which highlights that in the controversial process of globalization of the last forty years, Latin America was one of the clear losers.

"Most of Latin America has not been “globalized” or even internationalized. Brazil and Argentina remain two of the world's most closed economies, with trade representing less than 30% of GDP. Latin America and the Caribbean as a region is 11 percentage points below the world average (45% vs. 56%) in the importance of trade to its economies, and is a long way from the stars of emerging markets and developing countries. commercial rivals, whose trade flows can rival in size the GDP of the region as a whole”, he maintains.

That research adds central data on regional decline. For example, there has been no verifiable diversification in the production of local economies in the last 30 years. There was what economists call “premature deindustrialization”, that is, the reduction of the manufacturing industry as a percentage of the economy. “This economic depression contrasts with that of nations that were previously their peers. Mexico, Brazil, and Argentina have been overtaken by South Korea, Singapore, Malaysia, and Hong Kong, as well as many Eastern European nations. It is no coincidence that many of these countries have closed the wealth gap with the developed world, while Latin America as a whole has remained stagnant.

The explanations of this alley are multiple. It helps to look at some surprising facts. In Latin America, less than a fifth of trade takes place within the region itself. It is no accident that these countries have grown more slowly than many other emerging markets with stronger trade links with their neighbors, the report says.

The resistance to openings and expanding trade explains why there are only four crossings in the 5 thousand kilometers of border between Argentina and Chile and only one by train in Socompa. Or that only a third of the flights connect the cities of Latin America with each other. And finally, that of the 4 million companies in Brazil, only 24 thousand send their goods or services abroad.

It is not clear that these regressive schemes can be modified in the medium term. In a recent debate within Mercosur, Uruguay raised its own need, and eventually the group's, to negotiate a free trade agreement with China. Argentina opposed it more than anything due to the inertia of its extreme nationalist vision. But it should not have drawn attention that former center-right Brazilian president Fernando Henrique Cardoso and Lula himself joined in a document against that alternative. The only coincidence that these two men, who are allies, seem to have with the government of Jair Bolsonaro is that developmentalist and protectionist concept that looks with concern at any external competition.

Certainly there are elements that can justify such prevention. wowWhen the United States, from the administration of Bill Clinton and later with that of George W. Bush, proposed a hemispheric free trade agreement for the Americas, the FTAA, it was the Brazilian establishment that stopped it. The myth maintains that this pact was struck down by the Venezuelan Hugo Chávez together with former Argentine president Néstor Kirchner with the strident collaboration of soccer player Diego Maradona. The reality is that the São Paulo FIESP, which held the project's vice-presidency along with the United States, resisted with a central argument that a diplomat from Brasilia told this chronicler: "This agreement frees North American companies to participate in government tenders in the south, but it makes it difficult from the south to the north, it frees up the airspace in the south, but not in the north. It's like they make the screws and we make the holes."

The need for a modernization of the region has become pressing, even defying the protectionist exuberance. It is because there is a social tension that threatens the entire institutional building and a valve that glimpses some future is required. Many governments besieged by the crisis are turning to formulas that are certainly orthodox, as in the cases of Venezuela, Cuba, and more timidly, Argentina, to resolve the impasse. In a recent work of his own, this chronicler explained that the Cuban case is particularly complicated, also because of the symbolic load of that experience. La nomenklatura Islander has just lifted the ban on the purchase of dollars. There is a limit to the amount to be acquired, but the value of the US currency will be the one set by the market, 120 pesos per unit, well above the 24 pesos established by the monetary authority. Of course, this permit will trigger parity due to the urgency of Cubans to acquire the North American currency, which is practically the only instrument they have to fill their food basket. But it is a privilege of a few.

This movement, which is similar to the dollarization that Chavismo launched to try to escape its own crisis, is a central link in a chain that began to unite in January of last year when Havana unified its two currencies, the peso and the cuckoo Urgent of foreign exchange, she sought to make the island more interesting for international investors, mainly North Americans.

Raúl Castro, the younger brother of the late Fidel, then in charge of the government and the Communist Party, assumed that the arrival of Joe Biden in the White House would reverse the freeze imposed by the Donald Trump government against the rapprochement policies carried out by Barack Obama, the Democratic boss of the current president. It didn't happen. The former Democratic president had resumed ties with the island with the understanding that if windows were opened for trade and tourism by avoiding the blockade that has been in force for half a century, Cuba would enter into an internal political debate. There were signs to that effect. A middle protoclass had begun to emerge with micro and medium private companies that included commercial, air and naval openings, to and from the United States. But That path frightened the Cuban gerontocracy that celebrated with the North American hawks when Trump disrupted that rapprochement.

The truth is that monetary unification triggered the first devaluation in the history of the Revolution and drove an extraordinary rise in inflation up to three digits. From one moment to the next, the adjustment emptied the wallets of Cubans. There is the explanation of the historic marches of July 2021 in which people protested in the streets of half the country against the economic plan, against hunger and in demand for freedom and democracy as tools to solve those needs. The stalled regime downgraded those demonstrations to a US "coup attempt," a coarse and regrettable reaction to avoid acknowledging what was really happening. In addition, it aggravated the picture with colossal punishments for hundreds of protesters at a level that was not seen in Chile, Colombia, Ecuador or on other borders where there were also popular mobilizations due to the multiplied global economic crisis..

The repression has not calmed those tensions. It is convenient to look closely at Cuba. These internal pressures and frustrations are the same ones that are transforming the governments that we have already pointed out towards formulations that add tax force to the States, as in the case of Chile or Colombia, to alleviate central social debts such as health or education. In the Colombian case, especially, integrating a large part of the country that has never been contemplated in the distribution system and that explains the historical violence that has marked the present history of that country. These resolutions are crucial in a stage in which a form of protest is growing that, when configured, does not recognize rivals, advances above all.

Marcelo Cantelmi He is editor-in-chief of Internacional of the Argentine newspaper Clarín and director of the Observatory of International Politics of the University of Palermo.