The lost years

RAPHAEL POCH

Twenty years have passed since the publication of The Great Transition and almost forty since the beginning of the historical period it describes. When I wrote that book he was a young journalist still in the mental perspective of a long life. From that position I explained the title by saying that our present was, “a great time of change and universal transformation". "Time of changes”, was precisely the title of “The Great Transition” in its Russian and Chinese editions.

Today, having become a pensioner and much closer to the end of the brief vital journey that we humans have, my main point of view in this regard, what I retain when looking back, is no longer change and "transition", but the idea of wasted time.

If twenty years ago I wrote for readers more or less contemporary with what was narrated, today what is explained here is pure history for most readers. The passage of time changes perspectives, each generation rewrites history and uses the past to understand the present, with greater or lesser fortune, but the certainty of the great opportunity that humans let slip by concluding what was called the "east/ west” with the end of the cold war, has been placing itself in the center of the panorama these years, with great clarity. That was a test of maturity for the global north.

By declaratively canceling the dangerous tensions between powers, possibilities were opened for a change of mentality in the political and economic elites that would be capable of facing the challenges of the Anthropocene and the great dilemmas of North/South relations. Overcoming war and the threat of mass destruction as a method and last argument in international relations, seeking new criteria for collective security, abandoning the militarization of space, alleviating inequality between social groups and regions of the world to make it less unfair, tackling overpopulation , and, of course, addressing the climate crisis. That test, the global north failed resoundingly.

The US-led West continued to cling to its old imperial pathology. Favored by the Russian chaos, it simply occupied the geopolitical spaces abandoned by the withdrawal and dissolution of the Soviet Union, and sowed ruin and devastation in half a dozen countries. In the arc that goes from Afghanistan to Libya, passing through Iraq, Yemen, Syria and Somalia, entire societies have been destroyed in wars and interventions, direct or specific, which have displaced some forty million and have cost the lives of more than three million of people. The blockades and sanctions against old and new adversaries continue. The pretense of a solitary hegemony has dissolved diplomacy.

Instead of undertaking the necessary international concertation to face the challenges of the century, the global elites, and in the first place the Western powers, mobilize their societies to fight against their geopolitical rivals. In the great context of the relative decline of the Western power in the world and the transfer to Asia of a good part of that power, there is no more strategy than a reflex of panic, consistent with the well-known saying "The thief thinks that everyone is of the same condition. The West does not imagine that the supposed Chinese replacement on the command bridge could be different from the barbarism exercised by the Western imperial powers in the last two hundred years. If that were the case, only the worst could be expected, so the answer is to encircle the adversary militarily.

The war in Ukraine is, ultimately, a consequence of that encirclement and that Western mentality. The tensions created by the expansion of NATO and which served to justify the existence of this bloc that prevents the emancipation of the old continent, have led to a war to which NATO is responding with more expansion. A Russian war, with clear responsibilities for Moscow, and at the same time long favored by NATO, after which the pulse against the ascending power of China can be guessed, to which Russia has approached driven by the logic of the affirmation of their own national sovereignty and autonomy in the world. Since all the parties involved in this unfortunate situation are nuclear powers, the danger of a planetary disaster is enormous.

Putin's rise to power ended a decade of social ruin in Russia. With Putin, life stopped deteriorating for most Russians. Through this stabilization, the Russian President obtained a consensus that has more than compensated for his government's misdeeds and black chronicles, well known and widely reported in the West, but with the war and the devastating Western sanctions imposed against Russia, the bases of that consensus they are going to be radically swept away.

The purpose of the sanctions is not to pressure Russia to negotiate a settlement in Ukraine, but to "dismantle the Russian industrial power step by step" (Ursula von der Leyen, President of the European Commission), "bring to its knees", "ruin" and "destroy their economy" (The New Tork Times and the foreign authorities of Germany and England, respectively) and "make Putin go", in the words of President Biden. The goal is therefore regime change in Russia, but it is the Russian leadership who wants to govern that change, and certainly not in the sense desired by the West, but in quite a different direction.

First of all, the sanctions are going to harden the Russian political system. Existentially threatened, those who oppose the regime will be treated as “traitors”, Putin warned in a statement made less than a month after the start of the war: “The West wants to make us a weak and dependent country, violate our territorial integrity, fragment the country," he said. With that objective they rely on the "fifth column", those "national traitors who earn money here but live there, not in the geographical sense, but in the mental one, according to their conscience as slaves". "Those people are ready to sell their mother (...) but the Russian people will know how to distinguish true patriots from scum and traitors." "Such a purge will only strengthen our country, our solidarity, cohesion and willingness to face any challenge."

Secondly, the Western sanctions and blockades are going to transform the priorities of economic policy and foreign economic and political relations. Isolated from the West for many years, Russia will have to seek its life and economy outside the West, towards China, towards the BRICs, strengthening the "non-Western" pole of the world. Due to a geopolitical imperative, the sanctions oblige to sweep away or substantially modify neoliberalism and the rentier and parasitic capitalism of the oligarchs. They will force the introduction of more productive, more social and more authoritarian formulas similar to the Chinese one.

"The United States and the European Union have done what we should have done long ago: nationalize the economy of oligarchs: to hell with your western orientation, your holidays in the Alps and the Côte d'Azur and your shopping in Milan. The only thing that interests us is that they invest in the country and not export their capital to the West”, says the economist Sergey Glaziev announcing nothing less than “a new world” to 2024.

A new world or the beginning of the end for Putin and a new Russian bankruptcy? For the moment, in the first months of the war, the sanctions are still little felt in daily life and opinion polls offer considerable support for the invasion and for President Putin, between 60 and 70 percent. That support is not strong. "For our victory we will need a high level of mobilization in society and among the elite," predicts Sergei Karaganov, an organic intellectual of the Kremlin in the field of foreign policy. If the sociology of the last few decades has made one thing clear, it is that today's Russians are no longer that society predisposed to sacrifice their well-being and individual benefits on the altar of the supreme interests of the state. When Russians are asked in polls what they want for their future, considerations of their country's great power status and related issues are always at the bottom of the list, clearly trailing far more practical and pedestrian considerations.

Naturally, with the dissolution of the USSR, Russian nationalism and the multinational Russian identity in a broader sense have gained positions, but that is far from installing us in a passionate and fanatical universe, and in an economy of war, of will and mobilization behind a charismatic leader. Pragmatism and depoliticization is what characterizes the tone of Russian public opinion. Pragmatism in the sense that when faced with an unsatisfactory reality, the idea of acting to change it is not usually put forward, but the reflection of whether there is a clear alternative and whether the change will not lead to an even worse reality. Depoliticization in the sense that if the leaders and the President have made this or that decision, it is because they have compelling reasons for it. If that is the content, let's say conformist, of the high support for the invasion and for President Putin in the first months of the war, the most discreet thing that can be deduced is that this consensus is anything but firm and that it is clearly exposed to the volatility of the situation.

How will that consensus react to the calamities, deficiencies, shortages and radical changes in life that are announced? Before the collapse of the vital universe of the Russian middle class, before the possible return of the “deficit”, the disappearance of entire ranges of products? The sanctions, and the change in life for the worse that they will surely bring, topple everything Putin became popular for after the calamities of the 100.000s. How will the feeling of youth evolve? Many young people, about XNUMX in the third month of the war, most of them qualified, leave Russia for fear of military conscription (the same is true in Ukraine, but in Russia there is no hint of pathos patriotic) and to see themselves installed in a return to the gray monotony that their parents knew in the seventies of the USSR, “with aging leaders presiding over a failing economy, locked in a bitter rivalry with the West, relying on corruption and repression to keep the masses in line”, according to the graphic description of an Anglo-Saxon author. Is all of this crude, or is it imaginable, as Glaziev suggests, that the cardinal change in socioeconomic direction would make possible a structural transformation of the country that would put it on track for organic growth and establish a new social contract?

Be that as it may, things cannot continue the same, says Dmitri Trenin, a well-known Moscow political scientist: “En la war again kind that Russia is forced to free, the The division between what in previous times was called "front" and "rear" is blurred. In such a war, no and to win, but simply to maintain, it is not possible if the elites follow obsessed by further personal enrichment, and society remains in a state prostrate and relaxed. The "new edition» of the Russian Federation on basis politically more sustainables, economically efficient, socially more just and morally sounder, it is becoming urgently necessary. You have to understand that hestrategic defeat that the West our is preparing, it will not lead to peace and the subsequent restoration of relations. Most likely, the theater of "hybrid warfare" will simply move fromsde Ukraine further east, within Russia itself, whose existence in its present form will be in question", He says.

And, finally, when asked, can we imagine a middle ground between that disaster and the "radiant future" predicted? In any case, and be that as it may, regime change in Russia can be taken for granted and will be profound.

Rafael Poch He is a journalist and professor of International Relations at UNED. He has been a correspondent for 35 years, most of them in USSR/Russia and China.

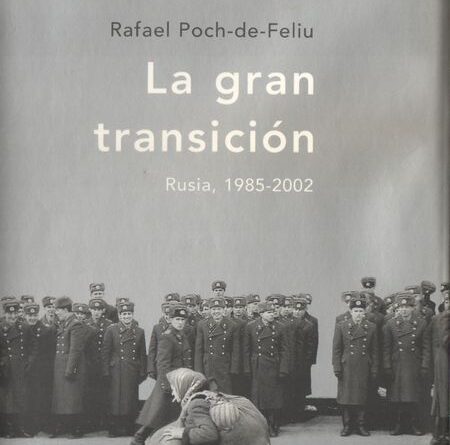

This article is part of the epilogue written by the author for the new edition of the book "The great transition".