The West's biggest misunderstanding towards China

XULIO RIOS

Probably the West's biggest misunderstanding of China is its strategic intentions. There are two ideas that sneak into any debate with hardly any discussion. The first is that China's success necessarily equals our ruin. The second is that this success leads to an exacerbation of conflicts. But let's see.

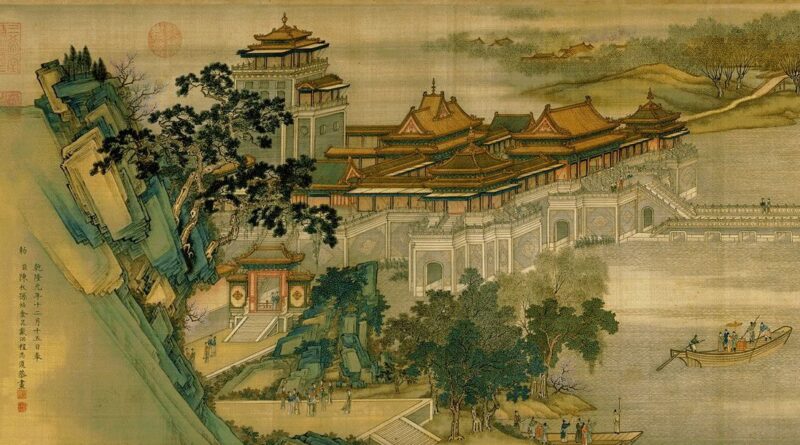

Certainly, China has managed to channel its modernization process, achieving many of its objectives. It has taken time and he has done it, basically, starting from his own efforts and generating important benefits for third parties. Sometimes, from what you read or hear, you could deduce that what was achieved happened overnight. But it's not like that. It starts in the 19th century, goes through the entire 20th century and will consume a good part of the 21st.

Getting rid of backwardness and underdevelopment is not an objective that can be simply discredited. Also the purpose of closing the wounds of that long and complex past. There have been well-known internal effects. Whatever parameter we choose, the jump has been spectacular. In 1949, the value of GDP corresponded to that of 1890, 60 years ago; In 1978, it was already the 32nd economic power in the world; now the second, the first in terms of purchasing power parity.

In the external effects, it can be seen that China is now more of a protagonist because it has more capabilities and can do more and contribute more to global needs. And there arises a first risk: there are those who think that this greater prominence is not a natural and logical consequence of success in modernization, but rather responds to a hidden agenda to dominate the world. Consequently, they refuse to make a proportional space for it in global governance.

The truth is, however, that if we look at what has happened in the last 50 years, the commitment to multilateralism has run parallel to the advance of modernization. From the return to the United Nations in the seventies to multilateral insertion in the post-Cold War, the promotion of own projects focused on development or security at the beginning of the XNUMXst century, and an acceleration of this process under Xi Jinping with new approaches ( Silk Roads, BRICS+ and the associated banks AIIB and NDB, among others).

Today, China practices a consolidated multilateralism with well-recognizable characteristics: multi-level, adapted, flexible, centered on a United Nations that it wishes to strengthen. It's about walking together, not in front of or against each other.

It is true that China develops its own discourse. It is a unique model for those who demand the respect due to their sovereignty - which cost them a lot to recover - but who does not wish to impose on third parties in an exercise of a messianic vocation. Despite this, he is accused of wanting to “reverse the international order.” If China simply accepted the narrative of the hegemonic club of powers, if it agreed to join the G7 (+1), for example, there would probably be no reason for discussion. Since this is not the case, double harassment arises focused on the defense of the architecture of the international order and, above all, of the hierarchy, which represents the true limit, the reddest of red lines for the West. In both aspects, a progressive erosion through factual means of the consequences of Chinese modernization is evident.

China actually wants stability and needs time and space to continue developing. A decisive section remains to be completed. That is why it can only bet on a peaceful transition in all areas, constructive, not abrupt but progressive, that both integrates its new dimension into the global reality and provides a precious margin of adaptation to other actors.

The insistence on sharing the benefits of your development is also a necessity of your own growth. This China is the most interdependent in its entire history, which is why it will never turn its back on openness, at the risk of falling back into suicidal isolation. That is why its success represents an opportunity for third parties. It may require adjustments, but there is a desire for a loose negotiation that accompanies the effects of the transformation that awaits us and on which they are already working, one would even say with a certain advantage over the West.

As also on a global level, its desire for stability is the opposite of the promotion of conflicts. It is not by chance that this community of shared destiny that its leadership promotes is based on pillars such as security, development or civilization. This last term, by the way, represents an enrichment of Deng Xiaoping's traditional formula, which marked peace and development as the preferred dilemmas of humanity. They are still valid, but civilizational preservation is a third dimension that denotes China's particular sensitivity in this aspect.

Despite systemic differences, there is much and substantial room for understanding between China and the West. Ignoring it could reveal perverse intentions.