A historic ruling puts a stop to lithium exploitation in Argentina

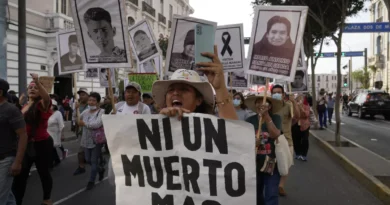

The struggle of indigenous peoples and socio-environmental assemblies bears fruit, which means a hard blow for lithium mining multinationals.

CECILIA VALDEZ

For years, the exploitation of lithium in Argentina has aroused enormous discontent among the native population due to its impact on the environment and living conditions. Following a demand from socio-environmental assemblies and indigenous peoples, the highest provincial court of Catamarca has prohibited the delivery of new permits for its exploitation and ordered that studies be carried out on the impact of all projects in the region, which means a hard blow for the lithium multinationals and the provincial government.

Lithium, also known as “white gold,” is an essential resource for batteries in electronic devices, and for the much-talked-about energy transition, which involves the replacement of fossil fuels (such as oil or natural gas) with others that allow reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

The triple border zone between Bolivia, Chile and Argentina (known as the Lithium Triangle), has high Andean salt flats and lagoons, which represent large mineral sources. They are also unique ecosystems and natural environments of great complexity and fragility, so the extraction of lithium by brine, which requires large quantities of water in areas that suffer water stress, complicates the living conditions in those places.

Native peoples and neighbors reject lithium mining due to its environmental and social impacts, and for violating indigenous rights in force in national laws and international human rights treaties. The Argentine National Constitution establishes that “the provinces have the original domain of the natural resources existing in their territory” (art. 124), and, in 1994, it incorporated a recognition of the pre-existence of indigenous communities and their community territories.

In this case, the violated rights have to do with prior, free and informed consultation, since the law establishes that those who are territorially involved have the obligation to be informed and access citizen participation mechanisms.

The historic ruling, which was known a few weeks ago, has a years-long struggle behind it and considered that there was “partially given place to the precautionary measure requested” in 2021 by the chief Román Guitián, representing the Atacameños community of the Altiplano de Antofagasta de the Sierra, against the national and provincial states.

The Court of Justice of Catamarca issues a ruling against the provincial government and requires it to correct the authorizations granted to mining companies for lithium extraction in the Salar del Hombre Muerto in Antofagasta de la Sierra,” explained lawyer Santiago Kosicki, in a note from the Tierra Viva Agency portal. In its resolution, the Court demands the preparation of a cumulative and comprehensive environmental impact report on the entire Salar and, in particular, on the Los Patos River.

The population's lack of water is one of the most immediate consequences that environmentalism denounces, in addition to clarifying that it is not lithium mining but water mining. The Puna (highland region) is a very arid ecosystem whose water reserves have been accumulating for many years. Companies extract without limits and dry up the basins, and, due to the lack of water in one place, they choose to take water from another.

This is what happened with the Trapiche River, when that source - from which 380 thousand liters of water were extracted per hour - was exhausted, the company Livent (in 2023 it merged with the multinational Allkem, creating the third largest lithic company in the world , which now operates in Catamarca under the name Arcadium), decided to move to the Los Patos River - which is the main source of water for the entire Catamarca puna - and build a new aqueduct there, 32 km from Trapiche.

"What we have in Catamarca, and in Argentina, is mining in salt flats, which are the lowest parts of the basins where all the water that runs off after the rain in millions of years ends up evaporating and taking minerals from all the hills. towards a single sector,” says Evelyn Vallejos, environmental manager and member of the Pucará organization.

The court ruling also establishes that the total impact of the companies that have requested authorization for the use and extraction of water, and their potential to transform the environment in the same geographical area, be considered.

Likewise, the new report must measure the impact of all the projects of all the companies together (and not each project individually), to know how much all the water withdrawals of all the companies will affect at the same time.

As the Graduate in Philosophy and member of the El Valle en Movimiento Assembly, Manuel Fontenla, points out, “this will be an enormous difference in the balance sheets and the result will be able to give, for the first time to the people of Antofagasta and the Indigenous Community, an idea of the size and the socio-environmental consequences of mining activity in their territories.”

Finally, the ruling highlights that the government of the province of Catamarca acts to the detriment of the regulations, and does not provide pertinent information to the population or guarantee public participation and consultation.

Regarding the national government, it indicates that it has failed to fulfill its duties by not guaranteeing the rights of indigenous peoples recognized in human rights treaties. He also considers that the affected community does not have updated information on at least eight lithium extraction projects in the same aquifer (Los Patos River Aqueduct), disqualifies the government from granting new permits to companies, and requests to suspend authorizations.