Alejandro Horowicz: Milei was left with the most degraded of the caste

CECILIA VALDEZ

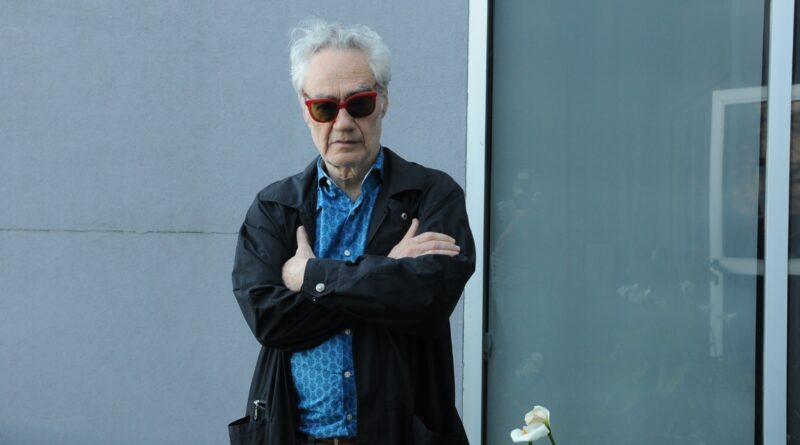

Doctor in Social Sciences, teacher and journalist, Alejandro Horowicz is the author of "The Four Peronisms" (1985), his most notable work and with numerous reissues. Critical and provocative are two of the main characteristics that are often used when describing him. Horowicz has written a latest book: 'Kirchnerism unarmed, The long agony of the fourth Peronism' (2023), in which he addresses the future of this force that emerged after the 2001 crisis (estallido/corralito), and which had as its main references, Néstor Kirchner and Cristina Fernández de Kirchner. In this talk with Globalter, he breaks down and analyzes the events of Argentine political history, both local and global, to find keys that allow us to elucidate how long periods of crisis and decline led to, and have as the most serious and main consequence, a government of the characteristics of Javier Milei's. According to Horowicz, this tells us about “a general systemic degradation, but also the degradation of Argentine society.”

How was it that someone like Milei was able to take over the presidency of Argentina?

When someone so particularly mediocre manages to win the presidency, what it lets us know is what exists on the other side. That is, what is the assessment that Argentine society has of its political leadership. Milei defeated the political system as a whole. On the one hand, you have an outsider, and on the other, the historical political parties of Argentina - which have between 70 years and more than a century of history -, dejected. So, it is very clear that Milei is the result of 40 years of parliamentary practice and a shared balance sheet. Furthermore, if you look at the poverty rates in Argentine history you realize that this is absolutely reasonable.

The title of your latest book is 'Kirchnerism unarmed, The long agony of the fourth Peronism', why?

The term disarmed has to do with a Clausewitz concept, which says that the objective of war is to disarm the enemy. This can be understood in many ways, the simplest and most obvious is to take away the weapon. Clausewitz is much more subtle and lets us know that, if a combatant loses his weapon, he is not necessarily unarmed. This means that if he retains the will to continue fighting, he will replace the weapon, and, therefore, he is not a loser. To defeat someone and disarm them is to take away their will for independent political action. This has to do, by the way, with the conditions of the fourth Peronism, because my work: 'El kirchnerismo disarmed', is, in some way, the continuation of a very previous work of mine in which I identify the Peronism that began with Carlos Saul Menem. That is the moment in which Peronism is completely surrendered and is no longer more than a party subjected to the general logic of national politics and, therefore, is nothing more than a party without a historical task. The fourth Peronism, of which Kirchnerism is nothing more than one of its manifestations, is that, simply the mode of adaptation to the global order as the global order imposes it. Because one can participate in the global order in many ways...

But Kirchnerism carries characteristics, or certain ingredients, of Peronism, and not just Menemism, right?

Without a doubt, they carry the ingredients of Peronism with several particularities, the first is that it stops containing the labor movement, and the second is that the labor movement stops being a political subject. That is, there are worker citizens who, as citizens, vote, but do not act as a class in any way or direction; when Peronism, in its previous versions, meant something else. So, the first ingredient is the absence of the labor movement. At this moment, the union leaders claim to be Peronists, but the workers do not. That is the first question, and that means, above all, a sign of belonging to a differentiated segment, because Argentina is a country with poor workers and rich union leaders. So, what you are seeing there is the phenomenon of political decomposition. That is, since we are not going to change the world or Argentina, we change cars. What you see is, basically, disinterest. When you look at the activity of politicians and see not what they have as assets, but what they recognize that they have, you realize that, first of all, there are no poor among the political leaders, and second, that, justifying what they do admit that they have, in most cases, is quite problematic. Consequently, this argument about the political caste that Milei states has enormous symbolic effectiveness because there is not the slightest doubt that they constitute a political caste.

You have dedicated a large part of your work to investigating Peronism, how do you see it currently? Do you think it will be able to reconfigure itself after the historic defeat last November?

The fourth Peronism is the Peronism of systemic defeat, that of defeat in the hands of Raúl Alfonsín first, and in the hands of De la Rúa, Macri and Milei, later. Basically, Peronism is a recessive current in national politics, and you see that by analyzing the numbers. You are talking about a blanket that shrinks from all four sides and that, basically, all it does, in its best attempts, is reconstruct fragments, because Peronism, as such, has exploded since the 2015 elections. In 2019 Of the six candidates there were, of the three presidential formulas with the most electoral chances, five were Peronists, and this means something. When you look at Milei's officials, and the Argentine political order, you understand that Milei was left with the most degraded part of the caste, that is, what has no place in any of the other political forces has a place in Milei's assembly. Most of the members of this government are people with no political tradition, or with a political tradition so long and so outdated that they were in winter quarters, but they are marginal to all other political forces. Consequently, what we are seeing is a general systemic degradation, which is also the degradation of Argentine society.

I understand, from what you have been saying, that Milei's legitimacy is sustained, in part, based on the delegitimacy of all the other political actors...

Your conclusion is more than correct, but it has one more wrinkle, and that is that Milei, if it means anything, is the delegitimacy of all the rest first. But the very particular legitimacy that we are attributing to it is 30%, the rest is the result produced by a ballot. The runoff fabricates a mandatory majority result and creates the illusion that 56% voted for it. Everything he put together after 30% is what was opposed to Massa, not what was in favor of Milei. That is to say, what Milei gathers is gathered in a ballot box and on social networks, just see that the mobilizations against Milei are already massive and the mobilizations in favor of Milei do not exist. Milei also comes out to greet an empty Plaza de Mayo, let's just say that he is not completely in his right mind, to put it very kindly.

I read an interview in which you said that “Argentine society has a catastrophic opinion of its political leadership and that, basically, there is an emptying of democratic practices replaced by empty concepts”, what exactly do you mean by that?

To the idea that politics is pure discourse, Foucault has a formula that I like to use that goes more or less like this, I quote from memory: “Revolutionaries believe that by changing the structure, the discourse changes, and reformists believe that that, by changing the discourse, the structure changes.” We know that a speech is a structure, the point here is the following: the idea that you can use a set of marketing formulas that, in certain circumstances, empathetically build a relationship with an electorate without solving any of the underlying problems that afflict them. to a society, and that this can be sustained indefinitely, is a very stupid idea. 2001 put an end to that possibility with the outbreak, and the Kirchnerist recomposition was nothing more than a recomposition of circumstances. Once the recomposition of circumstances is over, the degradation is more than clear. When Cristina leaves the government, there are 30% poor, when Macri leaves there are 35%, and when Alberto Fernández leaves, poverty is almost close to 50%, and that advances day by day. We are in an absolutely catastrophic situation, and with a catatonic society, which does not know what to think about almost anything, which has no price for things and which is moving towards hyperinflation after having sustained, throughout the last stretch of the century XX, two hyperinflations. In short, you are talking about a society in free fall, there are not many societies in the world comparable to Argentine society.

There are those who point out that what is happening also has its origins in a crisis of democracy as a form of representation. Do you agree with this assessment?

I believe that the forms of representation are closely linked to the ability to solve real problems. When one looks at 1970, one discovers the best distribution of income that existed in the planetary order. So, if we, with the labor productivity of 1970, much lower than the current one, without chips or computers, could have a much more equitable redistribution of income, it is very clear that a regression occurred, and that the last pandemic was not nothing more than an instrument used for global adjustment. I mean, with the pandemic not only did we not come out better, but there is an enormous increase in the precariousness of work, a decrease in real wages and a regressive redistribution of income. Under these conditions, the hollowing out of democracy in general, and the crisis of representation, go without saying. And this shows, among other things, the formidable tension that the European Union has, in which Britain not only leaves, and produces a catastrophe, but systemically threatens the Union. So, this is not a characteristic only of Argentina, in Argentina it occurs in pathological and much more intense terms, but it is nothing more than a general tendency of the world market with respect to the prevailing political order. We have a world government that is the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and a set of financial systems such as the European Central Bank or the Federal Reserve of the United States, which no one votes, but which basically decide what is done. throughout the world, simply with the device of monetary emission and the interest rate.

What place do leftist forces occupy in this whole framework?

None, the leftist forces, with the fall of the Berlin Wall, have suffered a huge regression. The defeat of the left is a global defeat, when someone talks about socialism they don't mean much, the speaker and the listener know that. The left is, basically, still, and in some places, a relatively ethical gesture, in others not even that. When one looks at Italian socialism, he sees a party as broken as the rest of the Italian parties. When you look at what happened to the French Communist Party and the Italian Communist Party, which were two enormously important forces in Europe in the '60s and '70s, not only do they no longer exist, but it is as if they had never existed. Those traditions are traditions that exist as political archaeology, not as political practices.

What way out do you see in this whole situation?

The outcome is very catastrophic, because we are not simply discussing what are the general conditions of existence of this or that segment of a society, but the very viability of existence. Capitalism produced Covid 19, and the miracle is not that it has produced one Covid 19, but that it does not produce three per day. They have destroyed habitat, and food production conditions are atrocious. This order of existence, as it is conceived, is unviable. The idea that oil or coal can continue to be used, as it is, or that the most basic and elementary agreements can not be respected, and that we go back and discuss again whether or not global warming exists, while In Europe the temperatures are devastating, it speaks of a suicidal global society. That's why the most terrible dystopia, seeing what world we go to after destroying this one, begins to sound simply like basic naturalism.

Cecilia Valdez She is an Argentine journalist.