Spain and China: reality and myth

XULIO RIOS

Next March 9 will mark the 50th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between Spain and China. From that already distant 1973 to today, a very important evolution of exchanges is verifiable, favored, among other things, by the mutual perception of being protagonists of parallel transitions that began almost in unison in both countries: in the second half of the XNUMXs, After the death of Franco, Spain began its "transition", and the same thing happened in China after the death of Mao, beginning the deployment of denguismo. In both cases it was something similar: a change of regime without a change of system. In addition, this common contemporary trajectory reached the common imagination of tragic episodes such as the respective civil wars, with unequal outcomes.

Over time, China has become an important economic partner for Spain, with a highly deficient external balance for Madrid. China is a reference supplier, the main origin of Spanish imports after surpassing Germany. On the contrary, for China, the Spanish market continues to be relatively insignificant, although with an image that continues to progress. In the investment order, Spain is not in the leading group of European countries that attract a greater volume of Chinese investment either, although they have evolved without major discrepancies. As is the case with exports, Spanish investments are not among the most prominent in China either. Both parties, however, grant significant potential to economic and trade relations and coincide in highlighting the persistence of windows of opportunity that could be exploited.

Since the 80s, the bilateral relationship has offered as relevant data the high level of political harmony between the two countries that has not suffered from the alternations in Moncloa. In addition to that transitional parallelism that caused a high level of reciprocal empathy, it could be argued that its foundation lay in what was known and respected before and is not now: the central interests of each party, whether we refer to territorial disputes or systemic differences. . Former Prime Minister Wen Jiabao referred to Spain on more than one occasion as China's friendliest country in Europe, it is often recalled. It is true that this reality did not do much to highlight Spain in the Chinese market, but it is fair to recognize that this is more due to the size and characteristics of the Spanish economy, which for China is not comparable in its interest to that of other countries in our around. Good political relations could lead to greater commercial benefits as long as the suitability of our productive fabric is strengthened. Where possible, there is a will for the relationship to move forward.

All this, it must also be taken into account, has had a long-standing cultural support with that moment of splendor between the XNUMXth and XNUMXth centuries and important references in outstanding figures such as Martín de Rada, Diego de Pantoja or Juan Cobo, the author of the first European translation of a Chinese text, a fact rarely valued.

In bilateral contact, China has also progressively consolidated a more accurate vision of Spain, usually very stereotyped. And, in general, the exchange has served for both parties to deepen mutual knowledge, although there is still a lot to be done in this regard. For Beijing, Spain is more than a destination of interest -not just a tourist one- due to its richness and diversity, although it does not come to conceptualize it as one of the main European or Western powers. The Hispanic singularity in the continental fabric, product of history and culture, would justify an exercise of specific diplomatic acupuncture that they consider viable and necessary in the community framework.

THE GEOSTRATEGIC ENVIRONMENT

But today, that referential Spanish position in China is losing importance and perhaps on the way to becoming a myth. Although both parties would like to maintain the core nature of that relationship, the current geostrategic environment threatens a certain level of cooling off. Therefore, that singularity that made the Sino-Spanish relationship something special in the European context seems to have its days numbered in light of the evolution of the geopolitical and transatlantic framework in which Spain is integrated.

It should be remembered that China and Spain signed a strategic association in 2005 that precisely reflected Madrid's status as a privileged partner in Europe. This meant that both parties subscribed to a common will to progress in the political dialogue and in the development of relations at all levels, sharing the same pragmatism. During the hard years of the economic and financial crisis, when the community troika induced Spain to apply severe austerity measures, China was there providing significant help, betting and investing (by the way, without demanding privatizations or cuts in health or education or nor express constitutional changes). This circumstance could have served to consolidate good bilateral relations and encourage a qualitative leap. Something like this, for example, occurred in neighboring Portugal, the object of a similar dynamic. In Lisbon, it resulted in daring decisions such as joining the strategic project of the Belt and Road Initiative, something that Spain rejected. Portugal, in fact, elevated that association with China to another higher level, equating itself with countries like Germany or France, a status that Spain does not have.

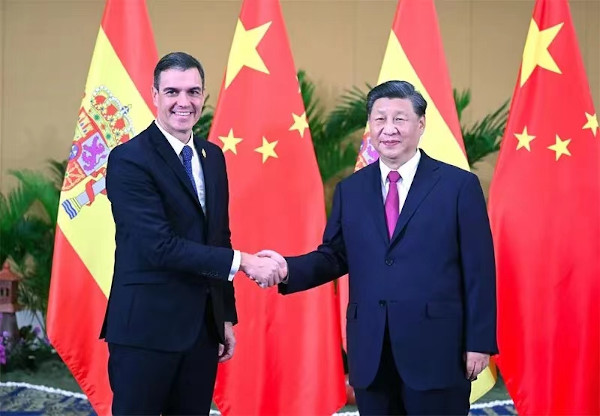

Xi Jinping's visit to Spain in November 2018, symptomatically, tasted like little. To a large extent, he already reflected the fears that threatened the horizon after the arrival of Donald Trump to the White House. A few weeks before that trip, Vice President Pence launched his ordeal against China as a warning to sailors.

The central question that is going to have a great influence on the future of Spanish-Chinese relations is the strategic change that is taking place after that US turn in policy towards China and that is dragging European countries more and more every day. Spain is not immune to all this and, consequently, the way in which Madrid relates to Beijing acquires greater complexity and subtleties that will inevitably affect the various sectoral components, whether we refer to commercial, cultural or, above all, political exchanges. .

Increasingly, the tone of the Spanish-Chinese relationship will depend on the general tone of the EU-China and US-China relationship. Bearing in mind that Spain claims to be an integral part of the "West" and that the pressure exerted by the US points to the repetition of a cold war this time with China to preserve its global hegemony, it is foreseeable that the complicity shown by Spain in the relationship with China is trading down in the coming years. It will be difficult for Madrid to escape this dynamic of growing interference from Washington that will force the European allies to choose a field. This will not only affect, as we have already verified, the technological options (Huawei's 5G, for example) but will cover all areas of special sensitivity as the bipolar paradigm is installed with greater impetus in the decisions of our governments. The intensification of this dynamic will make it difficult for the Sino-Hispanic relationship to take hold beyond what is foreseeable.

THE EUROPEAN PRESIDENCY

Traditionally, Spain has defended non-belligerent positions with China in the EU. During the semester of community presidency in 2010, Madrid announced the promotion of the recognition of China as a market economy or the lifting of the arms embargo, in force since 1989 as a result of the Tiananmen events. Already then, the pressure of the United States forced to moderate that enthusiasm.

In the second half of this year, Spain will again assume the community presidency. Against the backdrop of the war in Ukraine, China may be a hot potato if, as it appears, tensions escalate. What will be the position of Spain? Can he afford to deviate from Washington's hard line, or will he be the enthusiastic supporter of it? Given some axes of change in the Spanish foreign policy of the current government, there is room for surprise. The alignment with the community opinion regarding China (at the same time partners, competitors and rivals) offers a certain margin of slack. But the second half of this year will be especially tense in the Taiwan Strait. And although it does not support the most belligerent positions led by the Baltics or some PECOs (Central and Eastern European Countries), it remains to be seen that, as in the past, Spain can use the EU presidency to moderate the strategic scenario.

Therefore, the horizon that is envisioned in Spanish-Chinese relations points to a risk of political decapitalization to a degree to be determined. Spain must decide to what extent it wants or can include China in its global strategy and what level of flexibility it can manage, knowing that its market will continue to be of great importance and that this economy, despite the uncertainties derived from the restructuring process that lives globalization, will continue to present opportunities. On this trip, the political capital accumulated in the bilateral relationship will weigh less.