At the International Court of Justice in The Hague

CRAIG MURRAY

Today I attended the hearing of South Africa's case against Israel for genocide at the International Court of Justice. I have been able to sit in the public gallery and watch all the proceedings. However, the fact that we were not allowed pens or pencils (although we were allowed paper) prevented me from reporting. I asked the Head of Security at the ICJ why pens were not allowed in the public gallery. He told me, with a perfectly straight face, that they could be used as a weapon. Without my deadly pen, this story is less detailed and more impressionistic than I would like to offer you.

I arrived in The Hague early Wednesday, January 10, from Indonesia. I had to take four flights: Singapore, Milan, Copenhagen and, finally, Schiphol. I spent Wednesday frantically searching for warm clothes in the charity shops of The Hague, as I only carried beach clothes, apart from an old ski jacket from friends. I first called the ICJ to find out how to attend the Thursday morning session.

A young woman informed me that I had to queue in front of the small arched door in the wall. It would open at 6 a.m. and the first 15 members of the public would be admitted to the grandstand. I asked her where exactly she had to queue. She told me that she doubted it was necessary, that there was no problem in arriving at 6 a.m. on Thursday.

I'm staying in a hotel a five-minute walk away, so at 10pm on Wednesday, with the temperature at -4C, I went to see if there was a queue. There was no one. I went back to the hotel, but every hour I went to check if there was a queue I could join. There was no one at midnight or at 1 in the morning, but at 2 there were already 8 people, sitting in three very cold little groups. They all seemed very cold, but they were all friendly and talkative.

The first group, right next to the door, was made up of three young Dutch women, sitting on a blanket and well supplied with thermoses of hot coffee and boxes of baklava. The second group was made up of three young international law students, all Arabs, who had attended other cases and knew the trade well. The third group was made up of two young Arabs, one Dutch and the other Arab, sitting on a bench, looking cold and unhappy.

Soon we were all talking together and it was evident that we were all motivated by supporting the Palestinians in their fight against the relentless occupation. Shortly afterwards another Arab gentleman arrived, older and authoritative, who rather incongruously had studied in Scotland, at Gordonstoun. A tall Tunisian walking around making phone calls, he seemed worried and a little shy.

We had all received similar information about the number of people who would be admitted, although some had been told 15, others 14, and others 13. Our number remained stable at 12 for several hours. Then, around 4.30:6 a.m., a car pulled up and Varsha Gandikota-Nellutla of Progressive International got out. He had come as a companion to Jeremy Corbyn and Jean-Luc Mélenchon. Other members of his organization arrived little by little. As XNUMX a.m. approached, a small rush of people began to arrive, many carrying Palestinian flags and wearing keffiyehs.

It was very cold. After four hours, my toes had gone from hurting a lot to feeling nothing, and my fingers were no longer responding. Like so many other times, starting at 5 in the morning the cold became increasingly invasive. Mélenchon and Corbyn had arrived at 5.30 in the morning to take their places in the queue, Mélenchon as voluble as ever, wide awake, delighted to meet everyone, and lecturing on economics and the organization of society to anyone who met him. I would like to listen. Since my brain had already frozen, that didn't include me. Jeremy was typical Jeremy, worried about not taking anyone's place in line.

Then, when preparations began to open the door from the other side, things took an unpleasant turn. Those of us who had been there all night knew our order of arrival, but we began to be overwhelmed by the stragglers who were pushing us to get to the door. I had to be firm and try to organize the queue. Activists in the crowd objected and suggested that the entry criterion not be arrival time, but rather that Palestinians occupy the squares. One of the Dutch women, the first to arrive, accepted and gave up her place.

Everything became distressing. A Palestinian lady from Sweden who was just behind the 14th in line became deeply distressed at the thought of not being admitted, and a couple of Palestinian gentlemen who had arrived after 6 a.m. began pushing determinedly to get through the line. line. I made a little counter-speech explaining that we were all here to help the Palestinians, but none of us knew each other's stories, and the question of how helpful someone's assistance would be to the Palestinian cause was as important as gratifying feelings. individual of the terrible aggrieved.

The shy Tunisian was replaced in the queue by the former Tunisian president, whose position he had been occupying – a really nice and shy man, but the timing did not help the situation. In the end they admitted us in groups of five and processed us. One of the Dutch women who had been the first to arrive gave her place to a Palestinian. I left with my pass, number 9, went back to the hotel and went straight into a hot bath. The pain in my toes and fingers as they thawed was really unpleasant.

I rushed back at 9am to go through security, where they took my deadly wallets and pens. Then they accompanied us to the public gallery.

The Peace Palace was built by Andrew Carnegie, the extraordinarily morally complex Fifer, a vicious and incredibly successful capitalist monopolist who also wanted to end all wars and improve the lives of poor people everywhere. Its fairytale appearance, with the madness of tower perched on tower, belies its steel frame and concrete construction, and inside it could be any great City Chambers in Scotland, with majolica tiles and solid armitage stems in the toilets. Remarkably, the building is still owned and operated by the Carnegie Foundation.

For a building that was built as a world court, curiously it does not appear to contain any courtroom. The Great Hall is nothing more than a large empty hall that occupies a side wing of the building. A relatively modern, simple and gently curved dais has been placed along the length of the room, on which there was a long table and seventeen chairs for the judges, but the structure seemed provisional, as if the building had been taken and used for weddings. . The disputing parties sat in stackable chairs arranged in the body of the room under the dais, which also looked more like a wedding than a courtroom. Above the judges stretched an imposing stained glass window of garish colors and rather dubious quality.

I have written about my faith in the International Court of Justice, its history of fair trials, and its system of election by the UN General Assembly. The ICJ has been unfairly tarnished by the reputation of its much younger sister, the International Criminal Court. The ICC is rightly derided as a Western tool, but that is not true of the ICJ. In Palestine alone, it has ruled that the Israeli “wall” in the West Bank is illegal and that Israel has no right to self-defense in the territory of which it is the occupying power. He has also ruled that the UK must decolonize the Chagos Islands, a cause close to my heart.

Those of us who opposed the genocide had every reason to have traveled to The Hague with hope.

In addition to the court's fifteen regular judges, each of the parties to the dispute, South Africa and Israel, had exercised their right to appoint an additional judge. After the judges appeared in court, the proceedings began with these two judges swearing an oath of impartiality, giving us the first Israeli lie of the case before it even began.

The appointment of Aharon Barak as an Israeli judge to the International Court of Justice is extraordinary, given that as president of Israel's Supreme Court he refused to apply the ICJ ruling on the illegality of the wall, claiming that he knew the facts of the matter better than the ICJ.

Barak has a very long history of accepting all forms of repression of Palestinians by the Israeli Defense Forces as legal for reasons of “national security” and, in particular, has repeatedly refused to speak out against Israel's long-standing program of demolitions of Palestinian homes as collective punishment. This directly translates into the destruction of civilian infrastructure in Gaza.

Barak is considered a “liberal” in Israel in the constitutional struggle between the judiciary and the executive. But that has to do with the ability of Netanyahu's corruption to go unchallenged, not the rights of Palestinians. By appointing his apparent opponent Barak to the ICJ, Netanyahu has displayed typical shrewdness. If Barak rules against Israel, he can claim that his internal opponents are traitors to national security. If Barak rules in favor of Israel, Netanyahu can claim that Israeli liberals support the destruction of Gaza.

I guess we'll see this last statement.

I was sitting in the public gallery, and watching the seventeen judges occupied much of my time during the hearing. Much has been written about which path they will take. It is too easy to assume that they will be influenced by their national governments. That varies from one judge to another.

Chief Justice Joan Donoghue is a US State Department and Clinton hacker who has never had an original idea in her life and I would be surprised if she started having one now. She half expected her ropes to be visible, sticking out of holes in the room's magnificent embossed wood ceiling. But others are more disconcerting.

There has been no national elite more rabidly anti-Palestinian than the German one. Instead of channeling inherited feelings of guilt into opposition to genocide in general, they seem to have concluded that they need to promote alternative genocides to make amends. Added to this is that the German judge of the ICJ, Nolte, does not come from a liberal reputation. But friends in Munich tell me that Nolte has a particular interest in the law of armed conflict, and that he is a rigorous intellectual. His view is that his professional self-esteem and his intellectual rigor will be the key factors, and that only points in one direction regarding what the Israeli Defense Forces have so blatantly done to the civilian population of Gaza.

On the other hand, there is a Ugandan judge at the ICJ who one might assume would side with South Africa. But Uganda, for reasons I frankly do not understand, joined the United States and Israel in opposing Palestine's accession to the International Criminal Court, claiming that Palestine is not a real state. Similarly, India would be expected to support South Africa as a key member of the BRICS. But India also has a Hindu nationalist government prone to appalling Islamophobia. I have not found any evidence of Justice Bhandari's internal record on inter-community issues.

But it has been suggested to me that in this case now being presented to the world, the UN General Assembly may have shot itself in the foot by replacing that British judge with the Indian one, considered at the time as a triumph for the developing world in the ONU. What I want to say is that these issues are very complicated and that many of the analyzes I have seen, even from some dear colleagues, have been simplistic.

Not only is the Great Palace of Justice not set up as a courtroom, but, for a World Court, the public gallery is tiny. It extends along one side of the room, high enough to kill you if you fall over the edge of the balcony, and is only two seats deep. Furthermore, the theater-style seats are a hundred years old and about to fall down. Your butt is eight inches off the ground and the seats tilt so that your thighs are four inches off the ground and the whole contraption throws you forward and toward the edge. Instead of fixing the seats, the Carbegie Foundation has fixed a sturdy wall-to-wall cable above the balcony railing, which acts as a second railing and provides an extra 15 centimeters of protection.

With a third of the grandstand closed to accommodate the audiovisual screening and internet broadcast, there were only 24 seats available in the grandstand. We were 14 in the queue and the rest were for representatives of key NGOs and UN organizations, such as Human Rights Watch and the World Health Organization. They were allowed to carry pens, obviously because they were considered respectable enough not to kill anyone with them. In fact, I may have bought a pen for one of them at some point, of course just to help them. Or maybe not: nowadays it is very difficult to know what is considered terrorism.

South Africa began with statements from its ambassador and its Minister of Justice, Ronald Lamola, and did so with a bang. He expected South Africa to start with a soft speech about how much he had condemned Hamas and sympathized with Israel over October 7, but no. Within the first thirty seconds, South Africa had hurled both the word “Nakba” and the phrase “Apartheid State” against Israel. We had to hold on to our seats as they were collapsing. This was going to be something.

Justice Minister Lamola delivered the first memorable sentence of the case. The Palestinians had suffered “75 years of apartheid, 56 years of occupation, 13 years of blockade.” It was very well done. Before giving the floor to the legal team, the “agents” of the South African State, in terms of the Court's statute, framed the argument. This injustice, and history itself, did not begin on October 7.

There was a second important framing point. South Africa stressed that for the request for “provisional measures” to be granted, it was not necessary to demonstrate at this stage that Israel was committing genocide. It was only necessary to demonstrate that Israel's actions were prima facie likely to constitute genocide under the terms of the Genocide Convention.

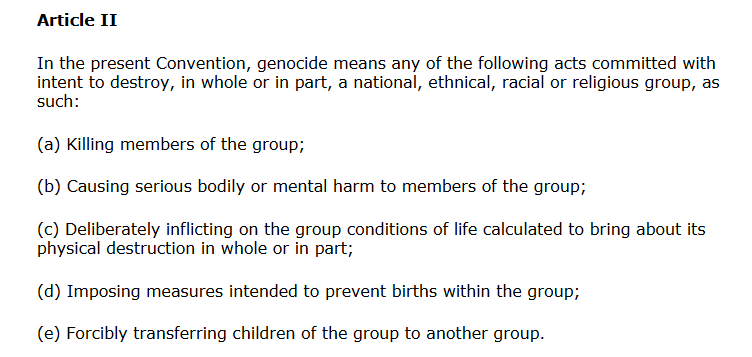

The legal team started with Dr. Adila Hassim. She explained that Israel had violated article II a), b), c) and d) of the Genocide Convention.

Regarding point (a) about the killing of Palestinians, he stated the facts without embellishment. 23.200 Palestinians were killed, 70% of them women and children. More than 7.000 were missing, presumed dead under the rubble. On more than 200 occasions, Israel dropped 2.000-pound bombs on the same southern Gaza residential areas from which Palestinians had been ordered to evacuate.

60.000 people were seriously injured. 355.000 homes had been damaged or destroyed. What could be observed was a substantial pattern of behavior that indicated genocidal intent.

Dr. Hassim was remarkably calm and measured in her words and presentation. But at times, when detailing the atrocities committed, especially against children, her voice shook a little with emotion. The judges, who were generally restless (more on that later), looked up and paid more attention.

The next lawyer, Tembeka Ngcukaitobi (today only South Africa intervened) addressed the question of genocidal intent. He had perhaps the easiest task, because he could recount numerous cases of senior Israeli ministers, senior officials and military officers referring to the Palestinians as “animals” and calling for their total destruction and the total destruction of Gaza, emphasizing that there is no innocent Palestinian civilians.

What Ngcukaitobi did especially well was highlight the effective transmission of these genocidal ideas from senior government officials to troops on the ground, who cited the same genocidal phrases and ideas to film themselves committing and justifying atrocities. He stressed that the Israeli government has ignored its obligation to prevent and act against incitement to genocide in both official and popular culture.

He focused especially on Netanyahu's invocation of the fate of Amalek and the demonstrable effect of that move on the opinions and actions of Israeli soldiers. Israeli ministers, he said, cannot now deny the genocidal intent of his plain words. If they didn't mean it, they shouldn't have said it.

The venerable and eminent Professor John Dugard, a striking figure in his brilliant scarlet robe, next addressed the questions of the court's jurisdiction and of South Africa's status in bringing the case; Israel is likely to rely heavily on technical arguments to try to give judges an escape route. Dugard noted the obligations of all state parties under the Genocide Convention to act to prevent Genocide, and the court's ruling.

Dugard cited Article VIII of the Genocide Convention and read in full paragraph 431 of the court's ruling in Bosnia v. Serbia,

Obviously, this does not mean that the obligation to prevent genocide only arises when the perpetration of genocide begins; that would be absurd, since the whole point of the obligation is to prevent, or attempt to prevent, the occurrence of the act. In fact, a State's obligation to prevent, and the corresponding duty to act, arise at the moment when the State is aware, or normally should have been aware, of the existence of a serious risk of genocide being committed. From that moment on, if the State has means that could have a deterrent effect on those suspected of preparing a genocide, or who are reasonably suspected of harboring a specific intention (dolus specialis), it has the duty to make use of those means to the extent circumstances permit.

I must confess that I felt very gratified. Dugard's argument was exactly the same, and he cited exactly the same passages and paragraphs, which my article from December 7 in which he explained why the Genocide Convention should be invoked.

The judges especially enjoyed Dugard's arguments, eagerly flipping through the documents and underlining things. Talking about thousands of dead children was a little difficult for them, but given a good jurisdictional argument, they were in their element.

Professor Max du Plessis then spoke, whose particularly direct and simple way of speaking brought new energy to the discussions. He said the Palestinians were asking the Court to protect the most basic of their rights: the right to exist.

Palestinians have suffered 50 years of oppression, and Israel has for decades considered itself above and beyond the reach of the law, ignoring both ICJ rulings and Security Council resolutions. That context is important. Palestinian individuals have the right to exist as protected members of a group in terms of the Genocide Convention.

The South African case was founded on respect for international law and was based on law and facts. They made the decision not to show the court videos and photos of atrocities, of which there were many thousands. Their case was based on law and facts, they did not need to introduce shock and excitement and turn the court into a theater.

It was a clever move by Du Plessis. The hearings were initially scheduled for two hours each. The South Africans had been told, very late, that it was increased to three because the Israelis insisted on showing their hour-long video of the October 7 atrocity. But in fact, the court's guidelines reflect a long-standing resistance to this type of material, which should be used "sparingly." If there are 23.000 dead, it does not add intellectual power to show the corpses, and the same can be said of the 1.000 dead on October 7.

Du Plessis concluded that the destruction of the Palestinian infrastructure that supports human life, the dispersal of 85% of residents into increasingly smaller areas where they continued to be bombed, were all clear examples of genocidal intent.

But without a doubt the highlight of the entire morning was the amazing performance by Ireland's KC Blinne Ni Ghràlaigh. His job was to demonstrate that if the Court did not order “provisional measures,” irreparable damage would occur.

There are times when a writer must admit defeat. I cannot adequately convey to you the impression he made in that room. Like the rest of the team, he avoided atrocity porn and stated the facts simply but elegantly. She adopted the tactic used by the entire South African team of not using emotive language herself, but instead quoting at length deeply emotive language from senior UN officials. Her description of the daily deaths by type of her was devastating.

I simply urge you to listen to it. “Every day one or more limbs are amputated in more than ten Palestinians, many without anesthesia”…

Now I should write more about the court. The South African delegation sat with their lawyers on the right of the court, the Israeli delegation on its left, each about 40 people. The South Africans were very colorful, with South African flag scarves and kefiyas on their shoulders. There was a mix of South Africans and Palestinians, including PA Deputy Foreign Minister Amaar Hijazi, which I was happy to see.

The South African delegation was lively and supportive of each other, with lots of inclusive body language and comparative animation. The Israeli delegation was the opposite of lively. She looked stern and disdainful, as if all her members had been instructed to get to work and were completely unaware of what was happening. They were generally young, and I think “cocky” would be a fair description. When Blinne spoke, they seemed especially interested in everyone seeing that they weren't listening.

From his body language, one would not think that Israel was the accused. In fact, the only people in court whose behavior was especially dubious and culpable were the judges. It seemed like they didn't want to be there. They seemed very uncomfortable, moved around a lot and fumbled with papers, and rarely looked directly at the lawyers who were speaking.

It occurred to me that the people who really didn't want to be on the Court were the judges, because in fact it is the judges and the Court itself who are being judged. The fact of genocide is incontrovertible and has been clearly stated. But several of the judges are desperate to find a way to please the United States and Israel and avoid rebutting the current Zionist narrative, the adoption of which is necessary to keep the elite's feet comfortably under the table.

What counts more for them, personal comfort, NATO's urgencies, future perks? Are they willing to give up any real notion of international law for those things?

That is the real issue before the court. The International Court of Justice is on trial.

During Blinne's intervention, the president of the Court suddenly became interested in her striking red iPad, the color of a particularly bright nail polish. This was repeated several times during the hearing, and I was never able to relate these appearances of the iPad to what had just been discussed: it is not that cases or documents had just been cited for consultation, for example.

The last speaker from the South African legal team was Vaughn Lowe, and he had the delicate task of countering Israel's defense, which they have kept secret from the court until it is presented. Rebutting arguments that have not yet been seen is a delicate proposition, and for me it was the legal tour de force of the entire morning. Vaughn Lowe's performance was outstanding.

He began by asserting that South Africa had standing to bring the case, repeating Durand's arguments about the duty of States to act to prevent genocide under the Genocide Convention. He claimed that there was a dispute under the terms of the Convention as to whether genocide had occurred or not. South Africa had framed this dispute in a series of Verbal Diplomatic Notes sent to the Israeli government and not satisfactorily responded to.

Lowe said it was recognized that a number of individual incidents were being investigated by the International Criminal Court as war crimes, but the existence of other crimes did not exclude them from being part of a wider genocide. Genocide is a crime that, by its nature, is often accompanied by other war crimes committed to promote it.

Lastly, Lowe said genocide is never justified. It is absolute, a crime in itself. No matter how terrible the atrocities committed by Hamas against Israel or against Israeli citizens, a genocidal response is not appropriate and never can be.

Vaughn Lowe stated that South Africa requested action against Israel and not Hamas, simply because Hamas was not a state and therefore not subject to the court's jurisdiction. But the fact that the court cannot act against Hamas should not prevent it from acting against Israel to prevent the current urgent danger of genocide. Nor should he be swayed by Israeli offers of voluntary moderation. The fact that Israel did not acknowledge any wrongdoing at all in its actions of “turning Gaza to dust” demonstrated that no guarantee could be relied upon that Israel would adjust its behavior, as it believed it had done no wrong.

The session ended with the South African ambassador reiterating the provisional measures that South Africa wanted the court to impose. These are:

(1) The State of Israel will immediately suspend its military operations in and against Gaza.

(2) The State of Israel shall ensure that military or irregular armed units that may be directed, supported or influenced by it, as well as organizations and persons that may be subject to its control, direction or influence, do not take any measures that promotes the military operations mentioned in the previous point.

(3) The Republic of South Africa and the State of Israel, in accordance with their obligations under the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, shall take, in relation to the Palestinian people, all reasonable measures within their power. to prevent genocide.

(4) The State of Israel, in accordance with its obligations under the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, in relation to the Palestinian people as a group protected by the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide Genocide, will desist from committing any and all acts falling within the scope of article II of the Convention, in particular

(a) kill group members

(b) cause serious bodily or mental injury to group members;

(c) deliberately subjecting the group to conditions of existence that will lead to its physical destruction, in whole or in part; and

(d) impose measures aimed at preventing births within the group.

(5) The State of Israel, in accordance with point (4)(c) above, in relation to the Palestinians, will desist and take all measures within its power, including the revocation of relevant orders, restrictions and/or or prohibitions to prevent

(a) expulsion and forced displacement from their homes;

(b) the deprivation of:

(i) access to adequate food and water

(ii) access to humanitarian assistance, including access to fuel, shelter, clothing, hygiene and adequate sanitation

(iii) medical supplies and assistance; and

(c) the destruction of Palestinian life in Gaza.

(6) The State of Israel shall ensure, in relation to the Palestinians, that its military, as well as any irregular armed units or individuals that may be directed, supported or otherwise influenced by it and any organizations and persons that may be subject to control, direction or influence, do not commit any of the acts described in paragraphs (4) and (5) above or engage in direct and public incitement to commit genocide, conspiracy to commit genocide, attempt to commit genocide or complicity in genocide, and to the extent that they participate in them, that measures be adopted for their punishment in accordance with articles I, II, III and IV of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.

(7) The State of Israel shall take effective measures to prevent the destruction and ensure the preservation of evidence related to allegations of acts falling within the scope of article II of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide; To this end, the State of Israel will not act to deny or otherwise restrict access by fact-finding missions, international mandates and other bodies to Gaza to help ensure the preservation and retention of such evidence.

(8) The State of Israel shall submit to the Court a report on all measures taken to give effect to this Order within one week from the date of this Order, and thereafter at such regular intervals as the Court may order. , until the Court issues a final resolution on the case.

(9) The State of Israel will refrain from any action and will ensure that no action is taken that could aggravate or extend the dispute before the Court or make its resolution more difficult.

With this, we close the argument. Next, Israel responds.