Before Gernika, it was Durango

The first bombardment against the civilian population in history turns 86

FERNANDO IÑIGUEZ

"We were in the church praying early in the morning, and suddenly we began to hear airplane engine noises and bombing noises. The little nun and I ran to the confessional to protect ourselves, but my other sister, Conchita, did not have time. I saw how some rubble from the roof of the temple and some beams fell on her head, leaving her body hidden under the rubble. We never saw her again, not even dead." That's how my uncle Nino told me, or at least that's how I remember him telling me, the most traumatic experience he had lived through in his life. He had not yet turned fourteen that fateful day of March 31, 1937, and it had not even been a year since the start of the Spanish civil war.

Durango was the forceful warning that the insurrection of General Franco and his comrades in arms, who rose up on July 18 of the previous year against the democracy and freedom of the Second Republic, were not willing to give up in their efforts to come to dominate Spain. whole at the cost of whatever. They would do anything to achieve it. That day, which is now 86 years old, also strengthened the support they had in two European allied countries, very strong at the time: Mussolini's Italy and Hitler's Germany.

It was mainly the Italian Legionary Aviation that perpetrated the massacre against that beautiful Biscayan town built at the foot of the intimidating Urquiola mount. A ferocious attack early in the morning, when he surprised my uncle Nino, his 12-year-old sister Carmenchu (the little nun years later, although it was not then) and Conchita, 10, and the mother of the three, Rosita; and another in the middle of the afternoon, when he was counting the damage, wounded and dead. By mid-morning there had been other inspection flights that flew over the city without dropping any bombs, focusing only on taking photographs of the damage caused and identifying possible new targets.

There was no mercy. The first of the attacks focused on the local churches and the market, knowing that most of the civilian population was concentrated there. The second, with fewer victims, was carried out, however, with more viciousness. The residents of Durango, believing that the Italian aviation had already done and finished its bloody work, came out of their shelters to try to rescue the injured and dead people from the early morning attack from the rubble. More defenseless, almost than in the morning, and more exposed, they were directly machine-gunned by the low flights of Italian planes, which also had the help of 14 German fighters from the Condor Legion that had departed from the Logroño air base to which At the front was Wolfram von Richthofen, cousin of the famous aviator known as The Red Baron, who Germany had exalted as one of its World War I heroes.

The terror bombings, which Hitler commissioned a few years later to the Red Baron's cousin, to devastate Europe during the Third Reich, began to be rehearsed by Commander Von Richthofen precisely in Durango, and it was the prelude to what would happen just three weeks later. in Gernika, a much more famous and remembered bombing than that of Durango thanks to the (sad) popularity that a famous Pablo Picasso gave it, expressing on a huge canvas all the destruction, pain and lack of humanity that a war always brings with it.

My uncle Nino sometimes told me stories of the Spanish war when I spent a few weeks with him during the summer of my university years. Nino, actually named Benigno, was a medical analyst in Burgos. Republican and anti-Franco to the core, he was, however, a man of conservative habits. A confirmed bachelor, a great smoker of rolling tobacco who pierced his shirts with his sparkles, he did not forgive a glass of gin to end his meals. His library was full of books on the Spanish war and the two world wars of the XNUMXth century. The laboratory had it in his own house. I remember him looking through the microscope, examining in small crystals what a drop of blood or urine did when he added his reagents, heating his test tubes over a bunsen burner, or accurately weighing the samples of whatever it was that he had to analyze. And writing down each data always in a notebook. I am not very sure if he would have known how to adapt to the computing that was yet to come and if he would have known how to order all that data afterwards. In return, while working in his laboratory, he used to listen, with great difficulty and poorly tuned, to the free radio that came from the other side of the Pyrenees.

A believing man, surely, even with his sins, he was a good Christian. Of those who, at least, don't know about hate. He complied with some of the rites of the church, and despite what he had experienced in his adolescence during the war, he did not express his grudge, probably because he did not have it, but it took him to hell to hear the benefits that were attributed to him on TV in each newscast , in the press and in the NODE to Franco and his regime. But what most unnerved him was that the official propaganda maintained that in the red spain from when the war, the faithful to the Republic, everyone was atheist and did not pray.

Durango was the example that that last statement was false. The hypocrisy of the Franco regime, to make matters worse, wanted to unofficially believe that the bombing of Durango had been perpetrated by Republican troops, and that is why they had attacked the Catholic buildings in the area. That, at the beginning of what happened, but since it didn't work out, a painful silence was forced later on about the bombing of Durango. It was better for him to be forgotten, for nobody to talk about him, the regime thought, lest "the feather duster be seen" and it is discovered that it really was the Italian and German planes coordinated by General Mola, in the operations that took place. during the war on the so-called Northern Front, to decimate the morale of the Republican side and in the face of the Numantine resistance in Madrid, which would prolong the contest until 39.

My uncle Nino was not carnal in the strict sense. He was my mother's first cousin, but since the bombing of Durango left him an orphan, my grandfather Jaime, brother of his father Alfonso, welcomed him as a son with his sister Carmenchu and took them to live with his family in Burgos. His mother, Rosita, died days later in the hospital due to injuries from the bombing, and his father, who was not in Durango that terrible day, died in the early postwar years after exile in the camps of Spanish refugees in France. So Nino and Carmenchu, the only survivors at the end, were like brothers to my mother and my uncles, their brothers and, therefore, as if they were also carnal to me. To further refute the false statement that the Reds neither prayed nor believed in God, Carmenchu became a cloistered nun, precisely in the Clarisas of Durango, the city where she had lived in horror as a child.

Nino, my uncle sometimes a bit of a curmudgeon - but who can't be living what he had lived through - lived without rancor. And even without being the joy of the garden, he was not a sad man tormented by a past that took away his childhood and who saw a little sister die without being able to do anything to avoid it.

But although he sometimes spoke to me about the war, he preferred to talk about the present –the end of the dictatorship then, the beginning of the transition-, or about his years as a medical student in Valladolid. Of course, he criticized everything about Franco and imitated him ironically, piping his voice and simulating the umpteenth inauguration of a swamp to the greater glory of the regime.

He only spoke to me a couple of times about the sad episode in Durango, as far as I can remember, but in his silences there was more desire to turn the page, to leave the hatred behind and not relive the horror, than to forget a sister or a mother. . Surely he preferred to remember them to himself.

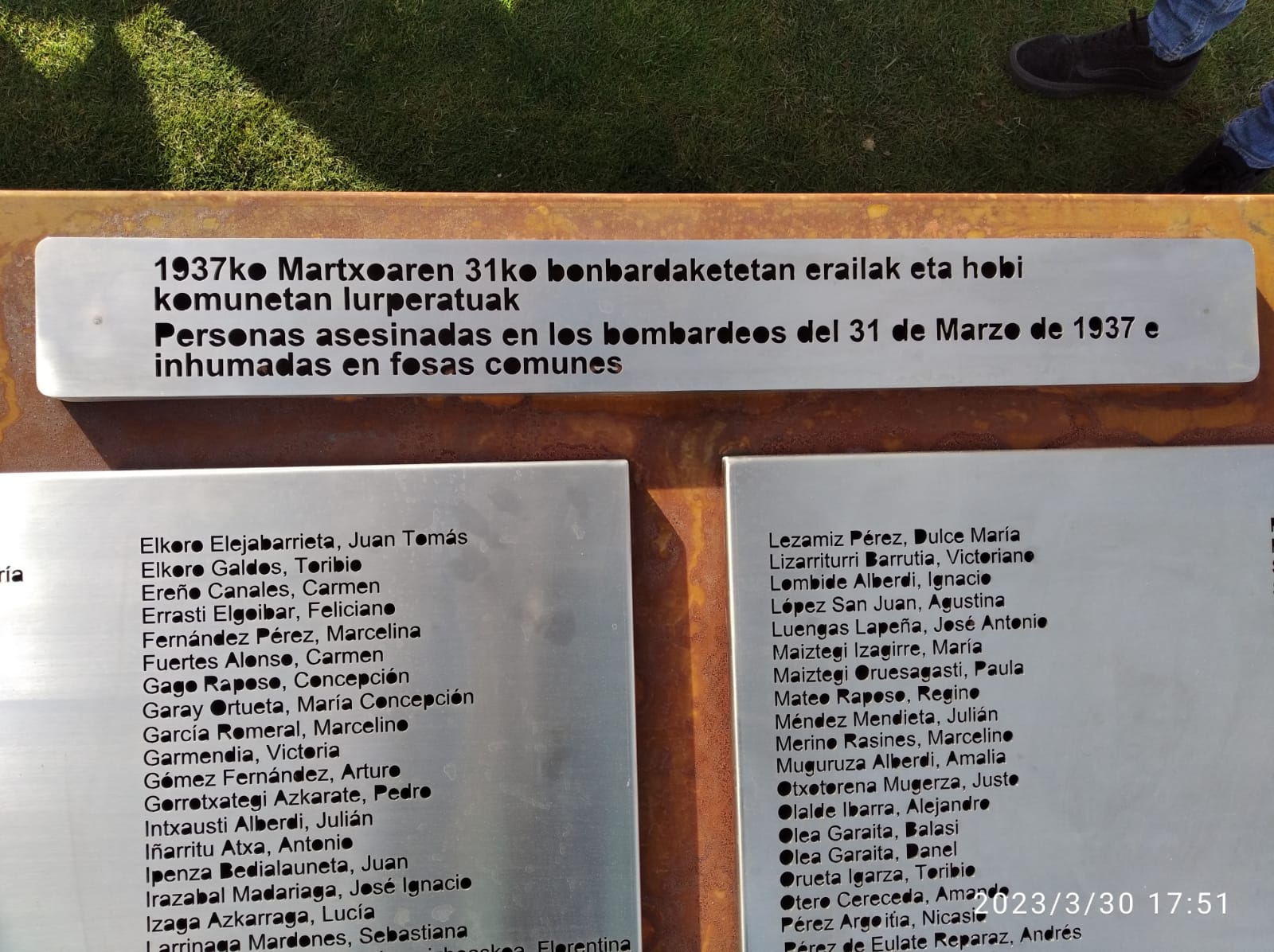

The people of Durango, however, have wanted to remember my aunt Conchita, even though she was never my aunt, since she died at the age of ten twenty years before I was born, and the other 336 people who officially murdered that March 31, 1937, raising a Memorial in the cemetery of that city punished so terribly 86 years ago.

The names of those 336 people have been immortalized on a plaque, and there they will remain engraved forever. Not so their bodies, which, despite the investigative work that the various historical memory recovery associations have carried out in recent years, have never been found.

Durango does not forget. In some corners of its streets they have posted photos of how they were left after the bombing to compare them now rebuilt: the town hall, the basilica, the market, the tailor shop... And in recent years, every March 31, at 8.30 in the morning and in the middle of the afternoon, in Durango the alarms sound again. Its roar reaches all corners of the city to remember the dead of that day. It is impressive to listen to them again, now, in times of peace. Imagining the chaos of then while they penetrate your ear, overwhelms and shudders. And they also sound like a threat or, better, like a warning: if history is forgotten, the horror can repeat itself.