Where is China going?

SABINO VACA NARVAJA

What does the statement made by North American President Joe Biden saying that the Chinese economy “is a time bomb” and the recent reaction of tycoon Elon Musk calling for tariffs or trade barriers to be imposed on BYD, the main Chinese electric car manufacturing company have in common? The answer is very simple: China alienates and confuses the West, which often adopts a vision distorted and somewhat capricious of the political and economic system of the Asian country, at the same time ahistorical and decontextualized, particularly in relation to what is happening with its economic growth, its productive system and its institutional structure.

Biden recites the repeated mantra of many Western analysts and media, who predict a fall of the Chinese model due to the fact that it is no longer growing as it did at some point after the economic reforms promoted by Deng. It is true, in recent years China has not grown at double-digit rates as in the first decade of the 2000s. But that has to do, in part, with corrections that have been made to the growth model promoted by those years. These analyzes follow the same structure as those that seek to hide that the Asian dragon economy represented a third of world GDP at the beginning of the Nineteenth Century, before the Anglo-Chinese war. Likewise, they also omit that, later and after a lot of water had flowed under the bridge, it was Mao who came to banish one hundred years of opprobrium and humiliation for the Chinese people and lay the pillars of the New China. As I wrote at some point, China has known how to adapt to the historical reality of each moment, giving itself the appropriate strategies for each situation.

In search of balanced and sustained growth

In this sense, and related to the supposed slowdown in Chinese growth in the last decade, I am interested in returning to the analysis made a few years ago by the Chilean economist Osvaldo Rosales who pointed out that Chinese leaders stopped trusting GDP growth as an indicator. univocal and sufficient economic advance. On the one hand, because growth at double-digit rates for almost four decades caused profound environmental and distributional deterioration, in addition to accentuating growth and well-being gaps between different regions of China. But, also and not least, due to the impossibility of projecting double-digit annual growth indefinitely.

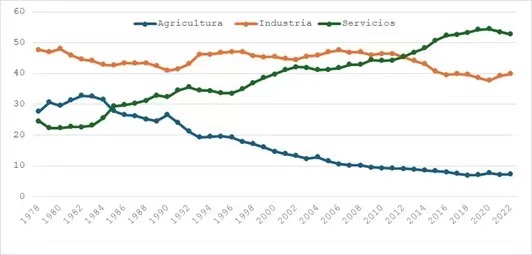

Another relevant point that the Chilean author mentioned is related to the structure of the product and employment. At the beginning of this century, China had to grow at double-digit rates to create the jobs necessary to keep the unemployment rate at bay, which were mostly linked to the manufacturing industry. Over the years, services increased their presence in the GDP. According to the World Bank, the service sector's share of Chinese GDP was 57,8% in 2022, and it employed about 48% of the workforce. Given that services are more intensive in employment, this means that today China can generate the necessary labor supply to allow the incorporation of new workers who seek to enter the labor market from one year to the next with growth at a lower rate, which Between 2016 and 2019 it was around 6% annual average. The graph below shows how the composition of GDP in China has changed since the reforms that allowed a profound change in the economic and productive system 46 years ago.

CHANGES IN COMPOSITION OF CHINA'S GDP (1978-2022, %)

Source: China Statistical Yearbook (2023)

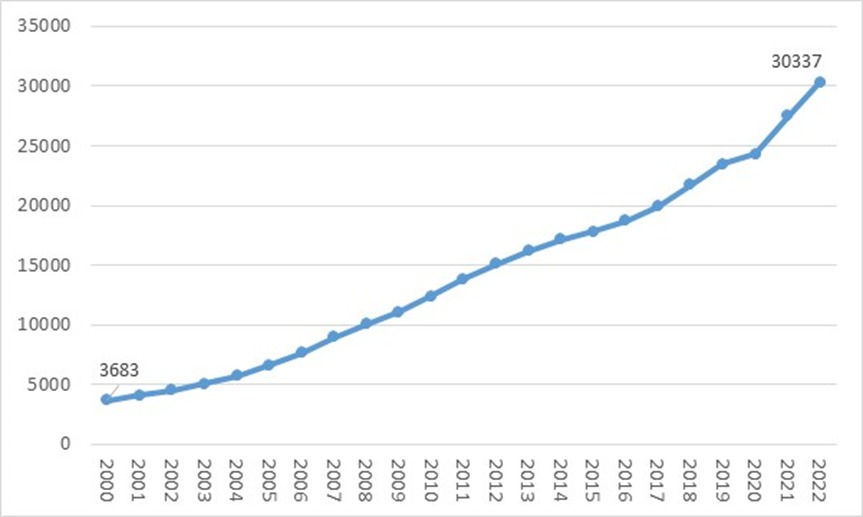

An additional factor that must be taken into account, says Rosales, is the scale of the Chinese economy and, in this sense, the impact it has on the global economy. He also added that, today, one point of Chinese GDP growth impacts world trade and GDP more significantly than it did about 15 years ago. The author explained that Chinese GDP had multiplied by 5,2 times between 2000 and 2018 and that, consequently, two tenths of Chinese growth in that last year had the same effect on the world economy as one point in the year 2000. The novelty is that in 2022 this ratio was 8,2 times, based on the same year 2000.

CHINA'S GDP AT CURRENT PRICES

(2000-2022, in US$ billions)

Source: Own elaboration based on World Bank.

However, we cannot fail to recognize the impact that the geopolitical and economic rivalry between the United States and China has on the international economy, which is reflected in the growing tensions around trade and technology policies and disputes regarding Intellectual property rights. Germany, to cite the case of an economy that despite surpassing Japan in third place in the world this year shows signs of stress, has been affected by lower Chinese demand, although this has not been the only cause of its lower growth. . By seventh consecutive year, in 2022 China continued to be Germany's first trading partner (according to preliminary data, this trend would have been repeated in 2023). Trade between both countries amounted to 279.000 billion dollars, equivalent to a year-on-year increase of 20%. German car manufacturers have an active presence in the Chinese market: Volkswagen makes almost half of its profits there.

I noted above that Chinese leaders stopped relying on GDP as an effective indicator for assessing economic progress. For a long time, the performance of local governments—provincial, municipal, prefectures, cities, etc.—was evaluated based on their greatest growth: based on this, the authorities of these administrations were rewarded by the central government with their promotion. In this context, these governments sought to grow as much as possible no matter what, promoting the wholesale sale of large areas of land to real estate developers for the construction of housing units and infrastructure works without it existing, as Rosales pointed out, the minimum analysis “of economic viability or social profitability”. To have a dimension of the matter, we must point out that in 2021 Chinese local governments derived 40% of their total revenue from the sale of land use rights.

The liquidation of the world's largest indebted real estate developer, Evergrande, ordered by a Hong Kong court at the end of last January, was something that could be seen coming. The Evergrande crisis affects more than 1,5 million home buyers, who are still waiting for the delivery of the promised properties for which they have already paid the aforementioned company.

The problem of the real estate bubble is not something new. Chinese President Xi Jinping himself, upon coming to power a little over a decade ago, took it upon himself to point out the importance of “common prosperity” and the need to take strong measures against “disorderly capital,” while rejecting real estate development as an investment and repeated as a slogan that “houses are to live in.” In China, where 70% of households are already homeowners and the average residential space per capita reaches 40 square meters, real estate supply far exceeds demand.

President Xi's government clearly detected the systemic design flaw inherited, in part, from the administrations that preceded him in power and in the past established measures to curb real estate speculation by restricting credit for overly leveraged developers and forcing these companies to keep your debt below 70% of your assets. Today, he has assumed an even stronger will in the face of financial vulnerability, especially with regard to the debt burden of local governments and the growing number of delinquent real estate developers. As he once pointed out, the priority for Xi is “stabilizing growth, readjusting the productive structure, promoting reform and favoring initiatives that benefit the majority” which is equivalent to “rooting out the evil that affects our long-term economic development (…) even when this means reducing the pace of growth” double digits, but at the cost of growing in an unbalanced manner.

Why the time bomb is not going to explode, as Biden predicted

As we all know, this is an election year in the United States and the Democratic president is seeking re-election. In this framework, Biden seeks to show his ability to boost the American economy in order to inject confidence in his potential voters. Beyond the battery of policies that the US president promotes to reinforce this aspect, the China issue will appear as a repeated catchphrase in the official narrative. Along with issues such as Chinese “economic and financial fragility”, the US discourse will recover the already reiterated rhetoric about democracy and human rights, the Taiwan question, the conflict in the South China Sea, as well as the issue of patents. and intellectual property and, especially, the current US administration will once again target a sector in which the eastern country has lately surpassed the United States, that of high technology. Especially when Biden's opponent in the November elections is former Republican President Donald Trump, for whom the priority in foreign policy is given by the challenge that Beijing poses to Washington for world hegemony.

Like the rest of the nations, China suffered the shock wave of Covid-19 which, as we all know, affected the entire world economy and triggered the biggest crisis in more than a century. However, as various analysts and even the International Monetary Fund (IMF) have observed, the speed of the country's economic recovery was notable, allowing China to take the lead among the main world economies. What's more, it was the only major economy in the world that grew in 2020 at rates unimaginable for other countries affected by the disease. Although later in 2022 China had a significant slowdown, this was largely a product of the collapse of real estate investment, which fell 10% year-on-year. The subsequent rebound of the Chinese economy during 2023, even above the target set by the government, greatly contributed to the global economic recovery in a direct and notable way. According to preliminary data for that same year, it would have contributed to a third of global growth, a figure in itself shocking.

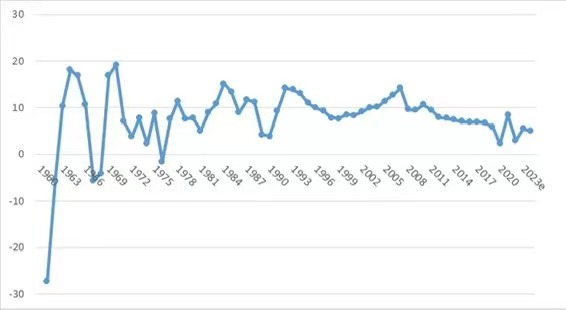

CHINA'S GDP ANNUAL GROWTH (1964-2024, % per year)

Source: Own elaboration based on World Bank. The chart includes estimated data for 2023 and the Chinese government's goals for 2024.

In a recent report, the IMF indicates that this recovery was driven by domestic demand, particularly by private consumption, as well as by favorable macroeconomic policies, such as a greater relaxation of monetary policy, the reduction of taxes on companies and households and fiscal spending to alleviate the effects of the natural disasters that the country suffered in the last year.

Despite the umpteenth omen of its collapse that the Western media and analysts predict, I perceive that good growth prospects remain for 2024 and even for the medium and long term. The growth objective for this year, which was just announced in the Two Sessions, will be 5%.

To explain it, I am going to base it on a very interesting article published by the Mercator Institute for China Studies in Germany, although the report reaches different conclusions than those I propose. Their authors rightly mention the change given by President Xi with respect to the norms of political economy that guided his predecessors: while the former were governed by an economy oriented to development, Xi's economy is oriented to geopolitics. However, this does not mean that growth and socioeconomic progress have ceased to be important for Xi, just as in the past, from Deng to Hu, the ideal of achieving technological development was always present.

I find the text very pertinent for the questions it raises, particularly when it asks where the Chinese government's efforts are headed to recalibrate the economy and achieve national rejuvenation in view of the centenary of the People's Republic, which will be celebrated in 2049. In order to achieve the growth goal, Xi and the CCP had to increase control and guidance over economic actors to direct them towards three main priorities:

First, Chinese leaders set out to achieve technological self-sufficiency and stabilize the supply chain, to prevent any other country from blocking China's access to resources, technology, capital or markets.

Secondly, China has made great efforts in recent years to reshape and diversify its international economic ties in order to expand its suppliers in order to guarantee a stable and long-term supply of raw materials. Likewise, it seeks to expand export markets and assume a central role in the global arena, especially with regard to the developing world. The Belt and Road Initiative, the largest economic project of the 21st century, as well as its financial complement, the Asian Investment and Infrastructure Bank (AIIB) and other measures such as the internationalization of the renminbi and the BRICS strategy of using The currencies of emerging countries are clear examples of Chinese efforts in this direction.

The third priority of Xi and the party leaders is to maintain and strengthen China's socioeconomic foundation. For the Chinese, development remains important. However, in recent years there has been a clear priority in managing risks in the domestic market. The main example is deleveraging the real estate sector instead of prioritizing uncontrolled growth, as we already mentioned. For this reason, to regain control of the economy, the provinces and local governments of China went from leveraging the aforementioned sector to doing the same with the technology sector.

For the current Chinese government, economic resources should be directed towards strategic sectors of the real economy, mainly high-tech manufacturing and emerging technologies, such as AI, biotechnology and semiconductors, among others. In parallel, some sectors such as real estate or consumer internet became considered non-strategic. For this reason, the CCP has established rewards and benefits for companies aligned with growth objectives: advantageous quotes, protection against foreign competition and access to all types of aid, from subsidies to cheap credit for small and medium-sized businesses. The Little Giants Initiative program is significant in this regard.

According to the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology of China, more than 10.000 companies fall into the category of “little giants.” By the middle of last year, about 3.600 newly certified small giants — of which 86 percent were privately owned — had obtained about 175.000 patents, according to a Beijing industrial institute. Of the 611 small giants on the list that had published their semi-annual financial reports, more than 90 percent showed profits. Meanwhile, 428 of them had invested more in research and development (R&D), and 17 increased their investment in that concept by more than 100 percent. All of these small businesses, based on R&D intensity, have proven to have powerful revenue-generating power and are promoted by the Chinese government.

Another economy that is being leveraged by the central administration is clean energy. A recent article places China as the world's leading supplier of key green components such as wind turbines and electrolyzers. China owns up to the90% of the European solar panel market and “is becoming the world leader and champion of electric car exports.”

It is clear that the Chinese government decided to move towards an economic model that revolves around innovation and technology. A model that ultimately responds to the objective of achieving more balanced and sustainable economic growth, which at the same time gives greater weight to activities with high added value. The obligatory question at this point is whether this is enough.

Economist Michael Pettis pointed out that economies with surpluses access surpluses mainly due to industrial policies that implicitly or explicitly force households to subsidize the manufacturing sector. It offers a fact that a priori might seem curious: while China accounts for around 18% of the world's GDP, it represents more than 31% of the world's manufacturing industry and less than 13% of world consumption, while the United States, which has the 24% of the world's GDP, it represents less than 17% of the world's manufacturing industry and almost 27% of world consumption. That said, he noted that in such persistent surplus economies, weak domestic demand is simply the flip side of the policies that make the manufacturing sector competitive.

For this reason, and despite the greater commitment to industrial policy, China is currently targeting domestic demand to avoid imbalances. The new 12-year growth plan aims to stimulate consumption and investment towards 2035, especially in sectors such as new energy vehicles and consumer electronics. Real estate investments are not outside of this plan, although clarifying that housing cannot be a speculative good so the Chinese State will meet a reasonable demand. An innovative feature is the one that refers to the “silver economy”, which aims to improve the care system for older adults, as well as benefits in financial plans for retirees and the promotion of medical research in the field of anti-aging therapies. Everything mentioned up to now is linked to the Chinese authorities' perspective of doubling their middle sectors in 10 years (according to the Boston Consulting Group, China will add 80 million more people to the middle and upper classes in the period between 2022 and 2030. In 2017, the middle class was estimated at 400 million).

A significant fact that accounts for the measures to support domestic demand implemented by the Chinese government is the rise of consumption during the Spring Festival. According to preliminary data, it is estimated that this year, during the forty days that the “chunyun” lasts, a record of nearly 9 billion trips sold would be reached. This figure—which triples the 2.980 billion trips in 2019, prior to the pandemic—is an indicator of the growing purchasing power of the population.

Also linked to consumption, the Chinese government has been promoting measures to reduce logistics costs and promote a renewal of equipment and an exchange of old consumer goods for new on a large scale with the purpose of promoting high-quality development and strengthening the real economy. To this end, it promotes at the household level the exchange of old automobiles, appliances and other durable goods for new ones, as well as technological modernization at the industrial level and in the services area.

On the other hand, we learned these days that the Chinese authorities are evaluating deepening the reforms, especially in the fiscal and tax systems. Specifically, it aims to address imbalances between central and local government structures.

Regarding the financial sector, guaranteeing its stability has become a priority, with special attention to the stabilization of the real estate market and the management of the debt of local administrations to prevent possible risks. This is not the first time that the Chinese government has gone out in search of viable solutions to the crisis in the real estate sector, in addition to establishing important controls on the sector as it has been doing for some time now. The good news is that the Chinese government has room to promote economic policies to strengthen demand, such as lowering mortgage interest rates, as well as commissions and other types of charges, or even making access requirements more flexible. to them. For that same reason, from time to time I do the counterfactual exercise of thinking what would have happened if the Evergrande crisis had happened outside of China and I answer that it would possibly have become a new Lehman Brothers. As happened in China, the crash could be cushioned internally and did not affect the stock markets of other countries with the consequences that this would have had for the global economy. When the subprime crisis occurred subprime back in 2008 or 2009, it directly affected American homeowners who were the ones who had incurred mortgage debt. On the other hand, here those who have a liquidity problem are the real estate developers. To this I would add that the debt of these companies is with the Chinese banking system and that the real estate sector, except for certain high-yield bonds, is financed mainly with national funds, which means that it has a low exposure to foreign direct investment ( about 4% in 2020). It is true, there is a real estate sector in crisis. But that crisis is not like the financial crisis that broke out after the fall of Lehman Brothers. Above all, because those in debt are companies and, furthermore, because the majority of real estate developers in China are financed with national funds.

In stock market matters, China has taken giant steps to implement a series of measures aimed at strengthening the market. The Hong Kong Stock Exchange's plans to connect with the savings of mainland China will mean that it returns to the top places in the world of finance, as before the US trade onslaught. To this end, in September 2022, a program was implemented to allow retail investors from China to buy international stocks in Hong Kong for the first time, which in turn makes the listing platform of this “autonomous territory” become more attractive to international issuers seeking to tap into mainland China's significant capital reserves. At the end of 2020, mainland investors were estimated to hold 205 trillion yuan ($28 trillion) in financial assets. By 8, that total is projected to increase at a CAGR of 2025%, to an estimated RMB 10 trillion ($328 trillion).

Another measure being discussed by authorities will allow mainland Chinese investors to trade shares listed in Hong Kong in Hong Kong dollars or yuan, simplifying settlement processes. In addition, this measure seeks to expand the channels of bidirectional cross-border circulation of capital in renminbi, promoting the long-term internationalization process of said currency.

Finally, the launch of Chinese Treasury bond futures in Hong Kong through the Stock Exchange will provide international investors with additional risk management tools in China's fixed income markets. Both this and the other mechanisms mentioned are of vital importance to help Chinese capital access global opportunities and promote the internationalization of the yuan, as we highlight.

For everything stated up to now, I allow myself to affirm that the Chinese economy presents promising prospects both in the short, medium and long term. As I have tried to argue, it is far from reaching a point of collapse. What's more, the risk is contained and the flourishing of certain industries does not suggest that there will be a serious economic decline.

I want to conclude this text by referring to an anecdote that involves Elon Musk, whom I mentioned at the beginning, and that tells us about China's ability to continue growing in an equitable and sustainable way. In a video recorded in 2011 that is circulating virally again, the South African tycoon is seen being interviewed by an oriental reporter. When she asked him if he saw the Chinese company BYD as a competitor in the development of electric vehicles, Musk reacted by bursting into laughter. The joke is that, in the last quarter of 2023, BYD surpassed Tesla not only as the world's first manufacturer of vehicles of this type but also in terms of international sales figures. What's more, it was recently revealed that the Chinese electric vehicle industry is purchasing huge cargo ships to overcome the transportation bottleneck to its global ambitions. China became the world's largest auto exporter in 2023 by shipping 4,91 million vehicles overseas, but until now it lacked the large cargo ships used by Japanese rivals such as Toyota. This logistical obstacle means that China has only 3% of the market in Europe despite the fact that its models are much cheaper than those of the competition. BYD, China's largest electric vehicle manufacturer, plans to buy eight giant vessels over the next two years. The first left port in mid-January and arrived in the Netherlands and Germany in February 2024. Meanwhile, poor Elon is pleading for tariffs to protect the US market from the Chinese cars he once laughed at.

Sabino Vaca Narvaja was Ambassador of Argentina to China (2021-2023) and Director General of International Relations of the Argentine Senate (2012-2015). He currently directs the Sino-Argentine Cooperation Programme at the National University of Lanús (UNLA).