The two receptions of the BRI

XULIO RIOS

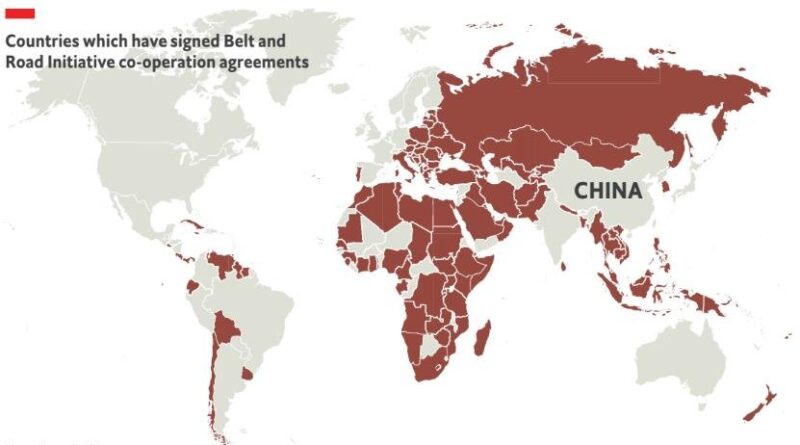

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) celebrates its first decade of implementation in 2023. The time elapsed supports it as a long-term project.

Two attitudes have marked the global reaction to it. On the one hand, developing countries have celebrated being able to have an alternative proposal that focuses on their most pressing needs, especially in terms of infrastructure. China's plan provides specific support in areas poorly served by traditional available financing, filling a gap of singular importance. The growth potential that China brings to these countries means, in many cases, solving bottlenecks that hinder the development possibilities of many economies. There is, therefore, a positive general evaluation, even though both parties, largely inexperienced in managing these new dynamics, must promptly adjust the management mechanisms and procedures.

On the other hand, developed countries have evolved from initial ambiguity and reservation to a certain competitive hostility. Actually, it's not smart to be afraid of the BRI; instead, China's strategy should be viewed with a broad vision and instead of dismissing it based on the supposedly “hidden interests” that inspire it, break it down in detail and explore the possibilities of triangular cooperation so that it can deliver universal tangible benefits .

In essence, the BRI could be understood as a proposal to enrich the globalization model promoted by the West based on the promotion of trade with the now introduction of other factors. This formula of Sino-globalization is seen by some as a “threat” that seeks the de-Westernization of the world; However, we also demand that the second largest economy on the planet assume global responsibilities.

The Chinese response points along these lines. Indeed, there is an empirical and transformative dimension to the BRI that pushes up the economies of the directly benefited countries. But the suggested spiral of stability and growth of some projects associated with the IFR creates opportunities for developed countries as well if they avoid acting in a lackadaisical manner. To achieve this, it is essential to recognize that the aid monopoly is over and that there are more players in the market today.

China proposes to developing countries to seek synergies that meet endogenous needs, that reconcile the interests of both parties, that generate trust, that improve strategic communication, that take into account the priorities defined sovereignly and without conditions, as well as the alternatives regarding the development model. The latter is a notable issue, since, on too many recent occasions, this has not been the approach supported by the Western-led multilateral institutions that have imposed neoliberal mechanisms with a very negative impact on the societies of developing countries.

And to developed countries, he proposes stimulating cooperation with third countries. Some have joined the AIIB (Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank) or even signed the memorandum of understanding. However, after the first five years of expansion of the initiative, the arrival of the de-globalization impulse of Donald Trump, seconded by the Biden Administration, has deduced serious obstacles to that cooperation by presenting China as a power-hungry rival.

It is surprising that in the reaction of the G7 or the EU there is more and more disqualification every day, the “we can do better”: G7 Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment and Global Gateway Initiative of the European Union, presented as an imitation, affect this narrative, which is actually confrontational, but it remains to be seen whether it can be accompanied by effective and ambitious proposals. A glance at previous promises does not invite optimism.

Developed countries do not celebrate China's contribution for fear that it will result in the reduction of their global institutional power. But development is a common concern and China can help narrow the gap. If what Western countries fear is that the BRI will drive the transformation of the international system by generating a new centrality, it is worth remembering that the shift of the global center of gravity towards the Asia Pacific is irreversible. Giving space and prominence is the only way to accommodate and integrate China into constructive participation in solving global problems.

The BRI is today a public good that demonstrates an unequivocal will to contribute not only to Chinese internal modernization but also to global modernization. China is inspired by its own history and tradition, and also by its different way of doing things, through consultation and negotiation, dialogue and relational governance. That China is of interest to the West and the world and without its projects – and its ideas and approaches – global governance is not possible.

A Galician politician from the thirties of the last century, Castelao, used to say: “don't hit the job until it's finished, whoever thinks it's going badly should work on it, there's room for everyone”. The same could apply today to the BRI. It's not about disqualifying, it's about sharing and improving.