The genocide of the Yanomami during the Bolsonaro government

CECILIA VALDEZ

At least 570 Yanomami children have died in the last four years "due to mercury contamination, malnutrition and hunger," according to the Ministry of Indigenous Peoples. After visiting the Amazon state of Roraima, the president of Brazil, Lula da Silva, declared a health emergency for the Yanomami Indigenous Land, inhabited by some 28 indigenous people. Lula maintained that what he had seen was more than a humanitarian crisis, it was a genocide, a premeditated crime by the Yanomami.

The emergency plan includes an operation to expel 20 garimpeiros (illegal mining mafias) from the territory; assistance to the Yanomami who suffer deaths from malnutrition and malaria, contamination of their rivers, invasion and devastation of the territory, sexual abuse and prostitution; and an investigation into Bolsonaro and several of his officials for omission that, if proven, could constitute a crime of genocide.

In mid-March, a Qaest-Genial survey indicated that 68% of the Brazilians consulted could not remember a single government measure since it took office on January 1, but those who did remember any mentioned the measures adopted around the Yanomami crisis. Lula has just completed 100 days in government, and although the polls continue to give him strong support, especially from the poorest social sectors (40%), he is still trying to find the necessary balance to govern.

Illegal mining on Yanomami land

The Yanomami reserve is located in the state of Roraima, in northwestern Brazil, on the border with Venezuela, and covers an area of more than 96 square kilometers (almost the same area as Portugal), although the total area, on both sides from the Brazil-Venezuela border, covers approximately 192 square kilometers.

By 2019, and according to data from the Special Secretariat for Indigenous Health (Sesai), linked to the Brazilian Ministry of Health, it was estimated that only the Brazilian areas were inhabited by some 28 people belonging to what the National Foundation for Indigenous Affairs ( Funai) describes as “recent contact peoples”. In other words, until the end of the 1910th century, the Yanomami only maintained contact with neighboring populations, and the first contacts with non-indigenous populations only occurred between the 1940s and 70s, as detailed on the website of the Brazilian Socio-Environmental Institute ( ISA). However, in the 1973s, the implementation of the "National Integration Plan", the opening of a section of the Perimetral Norte highway (76-1978) and the public colonization programs (79-1975), which took place during the different military governments of the time, paved the way for the invasion of Yanomami lands. In the same period, the RADAM Amazon resource survey project (XNUMX) detected the existence of important mineral deposits in the region. In this way, the publicity given to the mining potential of the territory unleashed a progressive invasion movement of gold prospectors.

Between 1987 and 1990, the number of garimpeiros in the Yanomami area of Roraima was estimated at between 30 and 40 thousand, some five times the indigenous population residing there. Although the intensity of the gold rush has decreased a lot since the beginning of the 20s until today, it is estimated that some 1992 garimpeiros inhabit -at least until the emergency declaration of last January- these lands that were declared an environmental reserve in 1.217. Illegal mining on indigenous lands in the Brazilian Amazon increased by 35% in the last 95 years, according to a study by the official National Institute for Space Research (INPE) released last February. In that period of time, almost all of the illegal mining activity in the Brazilian Amazon rainforest (1.236%) was concentrated on indigenous federal lands of the Kayapó, Munduruku and Yanomami peoples. In the last four years, under the management of Jair Bolsonaro, the area deforested by the garimpeiros went from 2018 hectares in October 5.053 to 2022 in December 2022. In 1.782 alone, they lost 54 hectares of their reserve as a result of illegal mining, the figure had risen 2021% since XNUMX.

The miners poisoned the water, the soil and the animals

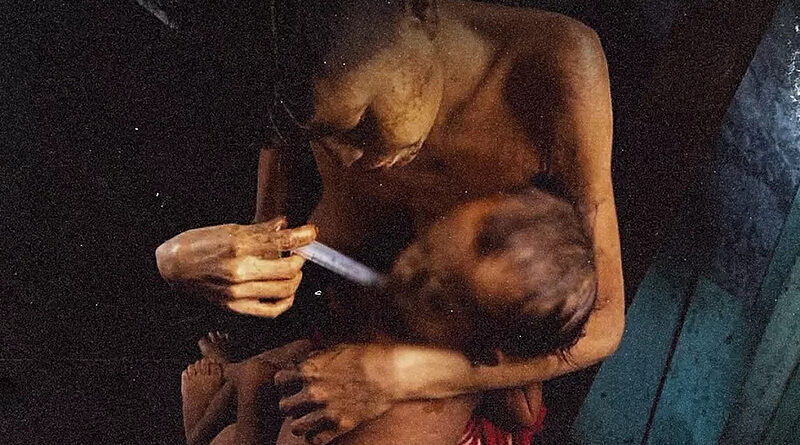

At least 570 Yanomami children have died in the last four years "due to mercury contamination, malnutrition and hunger," according to the Ministry of Indigenous Peoples, created by Lula and headed by indigenous leader Sonia Guajajara. The government confirmed that the main causes of death of 42 Yanomami indigenous people in the first two months of 2023 were malnutrition, diarrhea and pneumonia, all ailments associated with hunger.

Miners use mercury to separate gold dust from mud, poisoning the water and fish on which the community depends. A government analysis of four Yanomami rivers showed that they contain mercury levels 8.600% higher than what is considered safe. The Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), which has been providing technical support since the declaration of a health emergency last January, and is participating in a fact-finding mission to deepen knowledge of the situation and identify health care needs, warned of that contamination by mercury and other heavy metals has affected not only the rivers of the region but also the soil and animals, which has a direct impact on the diet of the indigenous people, based mainly on fish, fruits and collected roots, in addition to agriculture. He also said that this scenario has aggravated cases of malnutrition, acute respiratory infection, diarrhea, malaria and tungiasis among the Yanomami population. In response to cases of malnutrition in children, the plan implemented by the Ministry of Health, which includes the participation of indigenous health agents, promotes the preparation of therapeutic milk: water, powdered milk, sugar, oil, electrolytes, and micronutrient solution. . As a strategy to increase the acceptance of this milk among the Yanomami, local foods such as açai and banana were included in the formula.

Alcoholism, drugs and rapes

During his presidency, Bolsonaro received delegations of garimpeiros who asked for the cessation of controls to carry out mining on federal lands. According to different NGOs that work on the issue, the expansion of illegal mining responded to Bolsonaro's policies in the Amazon with indigenous peoples and to his rhetoric. In February 2020, Bolsonaro approved a bill that allowed mining and electricity generation in indigenous reserves and, according to Sumaúma -a news platform specialized in the Amazon-, that same year Bolsonaro was informed that the miners they had destroyed a Yanomami community and made no decision about it. At that time, a document delivered to the Yanomami Special Indigenous Health District (DSEI), an agency of the Ministry of Health in Boa Vista, denounced that mining had invaded the villages and caused violence, alcoholism and cocaine use among the indigenous people of the village of Kayanaú. . In the report, the health team professionals affirm that the garimperios used the region's indigenous health post and took medicines and vaccines that were for the Yanomami. The current government made the decision to dismiss 54 people, including 11 regional coordinators of the Secretariat of Indigenous Health (Sesai) and another 43 regional and state heads of the National Foundation for Indigenous Peoples (Funai), including 13 soldiers. The Minister of Human Rights, Silvio Almeida, assured that the mining mafia is also being investigated for having violated the human rights of girls and adolescents whom they allegedly kidnapped to subject them to prostitution and doing domestic work in the camps, in addition of the pregnancy of 30 indigenous adolescents who had been raped by garimpeiros.

In 2022, under the protection of Bolsonaro, businessmen seeking metals and precious stones increased their illegal activities in indigenous reserves by 46%, especially on Yanomami lands. In 2019, shortly after assuming the presidency, Bolsonaro maintained that during his government there would be no demarcation of indigenous lands and that "reserves hinder the development of the country." Along the same lines, he dismantled the public structure whose objective was to guarantee the rights of indigenous communities, and upheld this position not only on the domestic front but also in international forums, which resulted in a greater isolation of Brazil. During the administration of the far-right, both Norway and Germany distanced themselves from Brazil due to its environmental policies and withdrew their support, but after Lula's victory, and his promises to stop deforestation, both countries announced the unblocking of their economic contribution to the Amazon Fund, intended to finance environmental preservation projects. The Fund consists of about 576 million dollars and Norway is the main donor, since it contributes more than 90%.

"We will continue our support and we are also trying to mobilize other donors to join," the president said at the end of March. Norwegian Environment Minister Espen Barth Eide during a visit to Brasilia. His announcements are added to those of the German Chancellor, Olaf Scholz, who indicated in January that his country was willing to contribute 200 million euros - about 210 million dollars - to the Fund, and also those of the US, France and Spain.

Thousands of garimpeiros fled but their presence is still strong in some regions

The comprehensive plan arranged by Lula after traveling to the reserve last January includes emergency health care, food shipments, the withdrawal of illegal miners and the seizure of helicopters and other items used by the garimpeiros. The government detected at least 75 clandestine airstrips in Yanomami territory and ordered the definitive closure of the airspace as of April 7. In the early hours of April XNUMX, when the air corridors that allowed thousands of illegal miners to leave the territory were deactivated, the Brazilian Air Force (FAB) reported the destruction of a small aircraft used for illegal mining and the arrest of two people in a clandestine track near the border with Venezuela.

Although it is estimated that thousands of prospectors have already left the territory, these days images disseminated on networks by various associations linked to the issue, such as Hutukara Yanomami, evidenced the presence of prospectors who operate at night and bury the equipment during the day, in the Xitei region. Although these organizations recognize the actions carried out by the government in the last two months, they also demand permanent vigilance in the territories and denounce that in the regions of Xitei, Homoxi, Río Couto Magalhaes, Apiaú, Haxiu and the headwaters of the Mucajaí River , the presence of illegal mining is still very strong. In early March, a month after operations began, a Brazilian Senate commission announced that around 19 illegal miners had left the Yanomami reserve, and that some 800 remained in the territory.

Court orders that were not followed

In addition to the declaration of a health emergency in January, the government launched an investigation that seeks to establish responsibilities. The investigations are carried out by the Attorney General's Office (PGR), the Military Public Ministry, the Ministry of Justice and Public Security and the Federal Police. Before the Investigative Commission of the Senate, the attorney Alisson Marugal, from the Public Ministry of Roraima, directly related the omission of the federal government between 2017 and 2022 with the humanitarian crisis of the Yanomami people. He also pointed out that since 2017, the illegal mafia has acted uncontrollably in the territory and that in 2019 the Public Ministry, through legal actions, achieved some victories and demanded actions from the federal government that were not fulfilled.

The attorney also He referred to the sexual exploitation of minors and indigenous women and the distribution of drugs and weapons among the indigenous peoples, which, added to the contamination of the rivers and the impossibility of using the territory for planting, hunting and fishing, led to a humanitarian tragedy.

Marugal's statements were corroborated by the director of the Socio-environmental Institute, Márcio Santilli, who used the term genocide to refer to the omission of the government in recent years. Santilli thus joined a long list of officials of different ranks who considered that what happened to the Yanomami people could be described as genocide. This has been stated by President Lula da Silva, to the Minister of the Environment, Marina Silva, who argued that Bolsonaro should be investigated for genocide.

"Seeing the children of the Yanomami people in a situation of famine shows that it is a premeditated genocide," said Silva en an article published in the French newspaper 'Le Monde' while calling for international solidarity.

The Yanomami indigenous leader and vice-director of the Hutukara association, Dario Kopenawa, also said that to refer to the catastrophe that occurred under Bolsonaro's administration, he would use the term "onokãe", a Yanomami word that "means a genocide that kills people, sheds blood and kills lives."

Kopenawa explained that he had tried to bring "the voice of the Yanomami" to Bolsonaro's vice president, General Hamilton Mourão, but that those pleas fell on deaf ears.

The investigations are ongoing and from the Federal Supreme Court (STF), Judge Luis Roberto Barroso, ordered members of the Bolsonaro government to be included in the genocide investigation. The magistrate asked that the investigation determine if they committed crimes such as disobedience of judicial sentences and violation of secrets and environmental crimes to the detriment of the life, health and safety of indigenous communities.

Bolsonaro returned to Brazil on March 30 after 3 months in the US after missing Lula's handover of command. Now, in addition to the charges for genocide, he will have to face others that incriminate him for allegedly smuggling jewelry linked to the Saudi Arabian government.