The polls in Poland give a boost to Brussels and Zelensky

RICARD GONZALEZ

warsaw

Never before have elections in Poland been followed with so much interest beyond its borders, especially in Brussels, kyiv and Moscow. Two very different, if not antithetical, projects faced each other at the polls, both in foreign and domestic policy. The opposition's victory was received with relief and satisfaction both in the heart of the European Union and in Ukraine, although instead of a solution to its underlying problems, the result represents rather a lifeline of perhaps several months.

The victory of the heterogeneous opposition coalition was unexpected, both because it had not been anticipated by the majority of pre-election polls and because the electoral battle was clearly unbalanced in favor of the Executive. After eight years of authoritarian drift, the basic institutions of the State have been hijacked by the partisan interests of Law and Justice (PiS), a nationalist and ultra-conservative formation. The opposition victory will give hope to the opposition in countries like Turkey or Hungary, where a similar situation exists, and many doubt that it will be possible to unseat the leaders who have adulterated the democratic system to make a tailor-made suit.

Donald Tusk will almost certainly return to the post of prime minister nine years after resigning to become president of the European Council. His party, the center-right and liberal Civic Coalition, was the second most voted with 30% of the votes. The opposition coalition, which presented joint lists in the Senate, but not in the Lower House, was completed by Tercera Vía (center) and Lewica (ex-communist left) who took 14% and 8% of the votes respectively.

Law and Justice was left with the consolation of being the party with the most votes for the third consecutive election, an unprecedented milestone in the history of Polish politics. Specifically, he obtained 36% of the votes, a percentage significantly lower than the 43% eight years ago. Its only possible electoral partner, the ultra-liberal extreme right of Konfederacja, did not meet expectations and was left with only 7%.

Among the key factors in these elections, high inflation, government corruption scandals and fatigue with some PiS policies.

“In recent years, the Church has gotten involved in politics to support the government, and that is not good,” says Tomasz, an employee in the tourism sector. For this reason, Poland now has a much more restrictive abortion law, which has angered many Poles. “A key vote may have been that of women,” says Pocalca political analyst Marta Prochwicz-Jazowska.

The main and most immediate change will be in internal policy. The opposition coalition has promised to undo the path taken in the authoritarian drift of Law and Justice, and change a style of doing politics based on division and polarization. Now, the goal will not be easy. The three opposition parties have quite different ideology, and divergences could soon emerge. Furthermore, the institutions dominated by PiS will not make it easy for them. President Andrzej Duda, who is close to PiS, has the ability to veto Parliament's laws, and the Constitutional Court could rule against him repeatedly.

Indirectly, one of the winners are the EU institutions, which had repeatedly clashed with the Warsaw Executive to the point that several sanction processes had been initiated against them for violating the principles of democracy and Rule of law. In fact, as of today, Poland still has frozen the 36.000 billion that corresponds to it from the European fund to combat the effects derived from the pandemic.

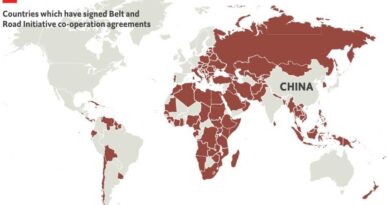

Specifically, the Government of “premier” Tadeusz Morawiecki had vetoed some important decisions, such as the migration pact, which requires the forced distribution of migrants arriving in the Union, and which is the main tool with which Brussels intends to address a crisis, the migration crisis, which seems to have overwhelmed it. Law and Justice defends positions that represent a threat to the European project, such as the idea that national law should prevail over community law. The Union faces decisive months, as it must close several substantial agreements before the elections to the European Parliament next year, including the reform of the institutions. Now, with the fall of Law and Justice, not all the wayward partners disappear, since Orban remains, and the eurosceptic Robert Fico, recent winner of the elections in Slovakia, could be added.

Likewise, the result also made many in Kiev smile at a time of unease as they see the growth of parties that want to reduce or withdraw support for the Ukrainian war effort, such as the AfD in Germany or, above all, the Republican Party in the US. . Although the Polish Government was one of the strongest allies of the Ukrainian cause for more than a year, in September relations between both countries soured as a result of the “grain crisis.” However, the problems come from afar, and are not only due to the Government's electoral interest in winning over Polish farmers by prohibiting the import of Ukrainian grain. In full escalation, Polish Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki even said that his government would stop sending weapons to the Ukrainian Army.

“There have been two problems for a long time. Warsaw hoped that kyiv would support its entry into the highest Western decision-making circles, which has not happened. Then, there are the conflicts related to the legacy of World War II,” says Prochwicz-Jazowska. Although Poles have enthusiastically mobilized to help Ukraine after the outbreak of war, relations between the two peoples have not always been cordial.

During World War II, Ukrainian nationalists fought against the Poles to make the eastern part of the country part of a future independent Ukraine. In fact, both Ukrainian and Polish nationalists committed massacres against the other community's civilians. The Polish Government has tried unsuccessfully to get Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky to agree to address the issue and admit Ukrainian crimes.

Now, the barometer of a possible loss of popular support for Ukraine should not be measured by the degree of support for the ruling party, but rather for the far-right Konfederacja formation, which not only advocates stopping sending weapons to Kiev, but even limiting aid to Ukrainian refugees. Finally, this party was far from what the majority of polls predicted, which predicted that it would hold the key to the governability of the next Government, with which it could have forced a definitive change in Polish policy towards Ukraine. Tusk will likely maintain the majority consensus in the EU on support for Ukraine. Zelensky has bought time, perhaps a few months, for his uncertain military offensive.