“The decarbonization of the rich is not ours”

CECILIA VALDEZ

Green colonialism or green capitalism is what critical environmentalism calls the exploitation of natural resources from the global North over the global South, and which will make it possible to guarantee the energy transition that industrialized countries boast so much about, that is, those that more pollute. But the energy transition requires natural resources that the north does not have, such as lithium or green hydrogen.

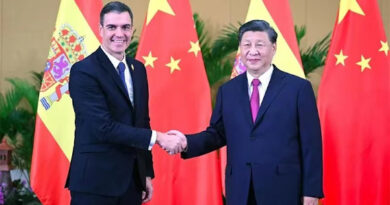

While the socio-environmentalist denounces the serious consequences of plundering practices, governments and corporations close agreements. Even countries that show irreconcilable differences in world geopolitics shake hands in their territories and seal commitments. On the side of Latin American progressives, the more or less critical position regarding extractivism depends on whether they are a government or not, and on the pressing economic needs that make them dependent on foreign currency.

"The decarbonization of the rich is not ours”, repeat those who inhabit the lands from where the resources are extracted. Lithium, also known as “white gold”, is an essential resource for batteries in electronic devices, and for the much-talked-about energy transition - accelerated by the War in Ukraine and the skyrocketing of energy prices -, which implies the replacement of fossil fuels (such as oil or natural gas) with others that reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

The triple border zone between Bolivia, Chile and Argentina (known as the Lithium Triangle), has high Andean salt flats and lagoons, which represent large mineral sources. They are also unique ecosystems and natural environments of great complexity and fragility, so the extraction of lithium by brine, which requires large quantities of water in areas that suffer water stress, complicates the living conditions in these places.

As pointed out in the report “The mine, the factory and the store”, by the Observatori del Deute de la Globalització (ODG), and whose work team visited mining exploitation areas in Chile and Argentina in December 2022, the 300 inhabitants of the Toconao community, in the southern part of the Salar de Atacama, can have a flow of no more than 4 liters per second, while in front more than 2.000 liters of water per second are extracted for lithium extraction. The population's lack of water is one of the most immediate consequences that environmentalism denounces, in addition to clarifying that it is not lithium mining but water mining.

Santiago Machado, from the Be Pe Civil Association (Catamarca, Argentina), agrees with the diagnosis: “this is the first time that in Fiambalá we are forced to buy water because of the smell of tap water; that was previously inconceivable. We are feeding a market that does not even benefit us, we are not going to use electric cars here. On the other hand, we do have agroecological, wine and food production.”

The energy transition also implies multiplying the extraction, which will consequently increase the damage. The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that demand will multiply by 42 in the next two decades. The other thing that is reported is that, although electric cars do not emit CO2 during their operation, they do so throughout the entire chain of extraction of their inputs, manufacturing, assembly and distribution.

The deforestation of the Amazon in Brazil, the lack of drinking water in Uruguay, forest fires and droughts are some of the most immediate consequences of the uncontrolled advance of extractivism. In addition to lithium, the other main protagonist of the energy transition is green hydrogen, which is obtained from water and renewable energy sources (wind mills or solar panels). One of the biggest doubts regarding hydrogen is the use of fresh water it requires, and that almost all of its production is intended for export.

Although environmental activism has been investigating and denouncing all of these practices for decades, now, in addition to confronting corporations and the most industrialized countries, they must confront a progressivism that adapts to the circumstances. It is, they point out, a new “environmentalism” disconnected from the territories, which, in the name of a supposed development that will benefit us all, does not question extractivism, and that, paradoxically, this occurs in Latin America, the region most unequal on the planet and where the maps of extractivism correspond to the places of greatest poverty.

In an article for Revista Anfibia, the sociologist Maristella Svampa opined that this environmentalism is more or less questionable depending on whether or not it is a government: “With some honorable exceptions, the anti-extractivist critique of really existing progressivism tends to settle in a space of variable geometry, since it depends on who is in charge of the national and/or provincial government.”

For Svampa, if it is a related government, that same predatory extractivism denounced a short time ago, ipso facto becomes a virtuous extractivism, that is, “national and popular”, despite the indignation of the environmental arc.

Precisely, where the largest lithium reserves in the world are concentrated, the so-called progressive governments of Luis Arce in Bolivia, Alberto Fernández in Argentina and Gabriel Boric in Chile coexist; all with differentiated strategies and policies regarding this resource. As the ODG report indicates, “unlike the Argentine and Chilean cases, where the main profits are accumulated by large transnational companies in charge of production, the entire surplus generated in Bolivia, although it is mainly associated with exploration and exploitation, remains within it, which is why the nationalist industrial model contrasts with the transnational commercial model in Chile and Argentina.”

In 2017, Bolivia created the National Strategic Lithium Deposits Bolivian Public Company (YLB), and declared fiscal reserves to the salt flats, so they cannot be exploited by any private company.

Argentina does not have a regulatory framework at the national level, and in 2011 the province of Jujuy officially declared lithium a strategic resource. A few weeks ago, the announcement of an express reform of the Jujuy provincial constitution, which aims to criminalize social protest and opens the door to large mining projects, with lithium at the center of the dispute, sparked a great popular rebellion that ended with hundreds injured and detained.

For many, Jujuy is nothing more than a laboratory for something that will later be transferred to the national sphere. The Argentine National Constitution (art. 124) establishes that “the provinces have the original domain of the natural resources existing in their territory”; this article makes it difficult to establish a unified policy on any resource.

For Svampa, "we are facing a perverse return of a false federalism that the 1994 Constitution generated by provincializing natural resources."

In Chile, on April 20, President Boric presented the National Lithium Strategy and announced the creation of the National Lithium Company, 100% state-owned. Although the organizations celebrated the possibility of a greater state presence in the production and distribution process, they denounced that it was developed with its back to civil society and the product of more than one hundred meetings with lithium businessmen and the electromobility sector, one of the businesses that generate the most expectations regarding the lithium industry in the region.

In recent years, Latin America has strengthened commercial ties with China in extraterritorial activities (installation of extractive projects), with large investments in energy and transportation infrastructure. China has a dominant position in the energy transition technologies market and a hegemonic presence in the different stages of the supply chain.

According to the ODG research, after China is the US, with an advantageous position because it can deal with most of the activities of the supply chain within its borders, followed by the EU with an import role due to its high dependence and, finally, the countries of the Global South that have a subordinate position through the extraction and export of their natural resources, with “a timid will to industrialize in countries like Chile, Argentina, Bolivia or Brazil.”

However, it is the large corporations, which are highly concentrated, who dominate the business worldwide and lead the critical mineral projects (Glencore, BHP, China Molybdenum, Tianqi Lithium, Jinchuan Group, Galaxy Resources, SQM, Zijin or Albemarle ).

For the sociologist and activist, Manuel Fontenla, the disputes for world hegemony -which occupy so much space in the political arena- are practically foreign to corporations.

“I think it is one of the false discussions that the hegemonic media take us to. While politics debate whether we should ally with China, the US or the EU, lithium transnationals merge regardless of the nationality of their constituents. If you analyze in detail who makes them up, you see that there are countries that on a purely political level may not defend the same interests, but in this case that does not matter. What we see is that international capital is very fluctuating and, when they have to supply a raw material, they make the necessary agreements and move forward.”

Numerous documents show that corporations have taken it upon themselves to install a sustainable mining discourse that legitimizes their actions. In 2002, Fontenla pointed out that the 'Mining, Minerals and Sustainable Development' (MMSD) program had recommended to companies in the mining sector a 'cultural change', which would allow them to build an imaginary of 'Sustainable Mining'. The aim was to guarantee the coexistence of mining development within a language of sustainability, despite the resistance that came from climate alarms.

Fontenla does not hesitate to affirm that this was achieved, but also that indigenous communities have updated their languages to counteract these ideas. Both Svampa and Fontenla maintain that in Jujuy it is no longer questioned who owns the lands from which the native populations were dispossessed, that this is a victory for the communities, and that this is evident in a change in discourse.

"There is no longer talk of anti-mining, but talk of a fight in defense of water and life," Fontenla points out. “The other thing that appears is the idea of good living, which is part of the worldview of indigenous peoples and is an idea that greatly strains the consumption system of capitalism, the idea of waste.”

In his experience as an environmental activist, Fontenla maintains that it is the struggles of the communities that have managed to eradicate mega-mining projects, which defend their territories and their autonomy, and not the protection laws of the State or international agreements.

For the environmental lawyer Enrique Viale, "socio-environmentalism is a great dispute of meaning", and it is necessary to break the "extractivist consensus" that places Latin America as a provider of nature for the global north as if it were a destination and not, as what it is, a global geopolitical decision.

But the lawyer is aware that "breaking with the 'consensus' requires a lot of determination since opposing it "has a high cost because ridicule and 'cancellation' are the weapons to maintain the status quo."

Until relatively few years ago, the discussion on climate change was seen, and pointed out, by broad sectors of the population, as an elitist discussion, exported from rich countries, since 'here' there were other emergencies, such as hunger or poverty. “The truth is that Argentina with fracking, agribusiness and mega-mining has more than half of the kids below the poverty line. It does not seem reasonable that by deepening this model we are going to have different results”, says Viale.

"There is a mechanism that works very well, which is to put some truth in the midst of many lies”, concludes Fontenla. “You have to be very attentive to be able to separate those things. The energy transition is real, but what we have to understand is that this level of consumption does not correspond to the energy available in the world, so we are talking about a crisis of a model, of the current capitalist production model.”

For the EcoSocial and Intercultural Pact of the South, which is an initiative of people and organizations from different Latin American countries: "Small changes in the energy matrix are not enough" (...) "relations must become more equitable not only between the countries of the center and the periphery, but also within countries, between the elite and the people (...) "more than just technological, the solutions to these interrelated crises are above all political," they point out.